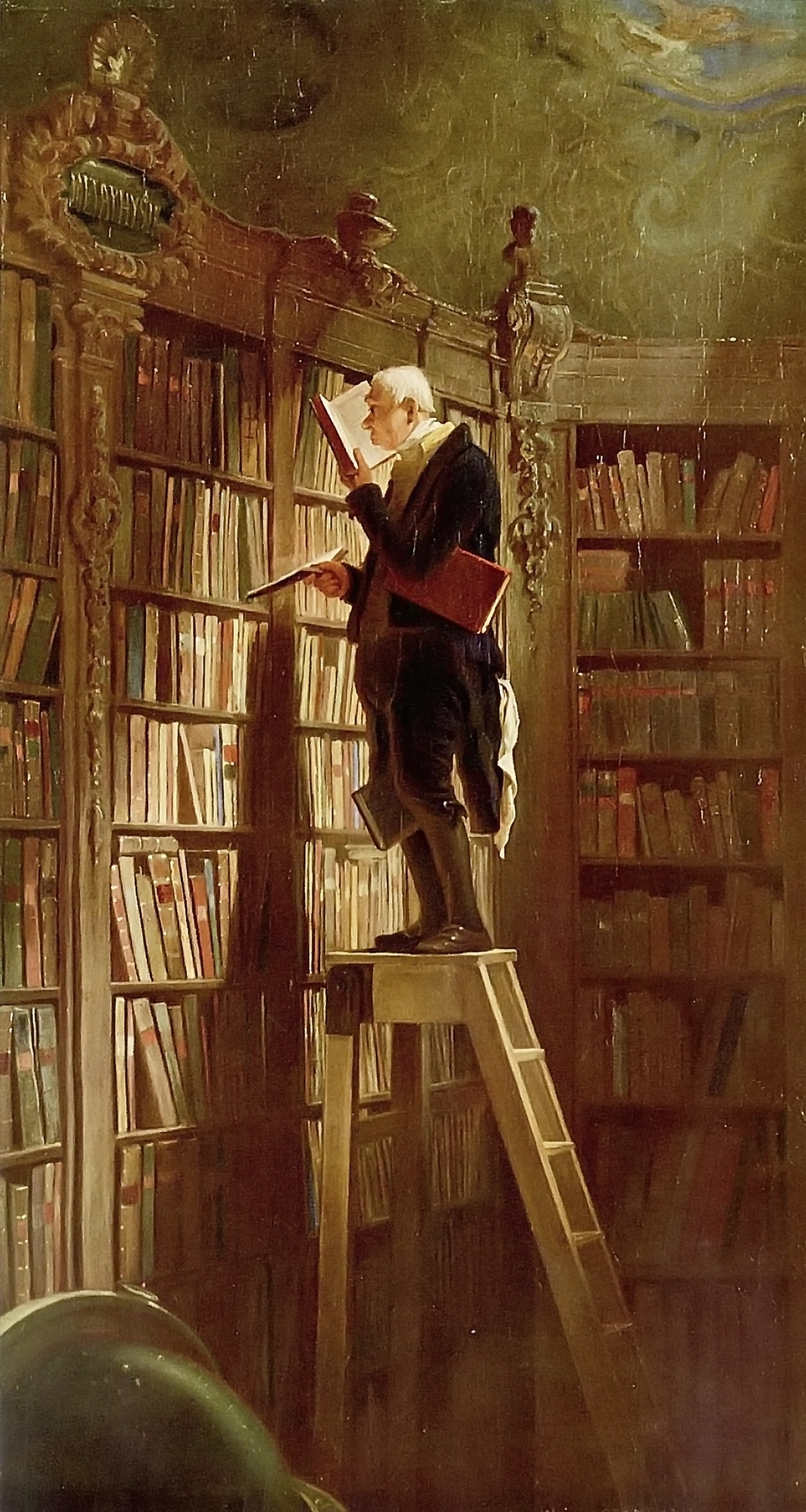

William Hamilton Drummond

Humanity to Animals, the Christian’s Duty

「1830」 William Hamilton Drummond, Humanity to Animals, the Christian’s Duty; a Discourse (London, 1830); 「partially extracted in The Voice of Humanity: For the Communication and Discussion of all Subjects Relative to the Conduct of Man Towards the Inferior Animal Creation by the Association for Promoting Rational Humanity toward the Animal Creation 1 (1830-Nov) 55-61; Google Books: Online Library of Free eBooks.

“Those who allow oppression share the crime.” If we hear or know of any existing cruelties, are we blameless if we do not endeavour to effect their extinction! Can our kitchens, our larders, our festive boards, testify nothing against us? We know them not—we hear them not. No; we take care to shut out from our eyes and our ears whatever would offend. We dread the pain of having our sensibility wounded, and hence the evils we should be instrumental in redressing are allowed to grow and multiply. They who, in the days of the Prophet Amos, ‘lay on beds of ivory and stretched themselves upon their couches, and ate of lambs out of the flock, and the calves out of the midst of the stall, and chaunted to the sound of the viol, and drank wine in bowls, and annoited themselves with the choicest unguents, grieved not for the affliction of Joseph.’ While we ‘eat the fat and drink the sweet,” we never, for an instant, reflect on the animal suffering which proceed the banquet:—the barbed hook, the lacerating shot, the shrieks, the groans, and the dying agony. Such reflections would embitter the taste; therefore they are excluded as enemies of our peace, and cruelties continue to be perpetrated, not because we approve of them, but because we allow ourselves to become even unconscious of their existence. (56).

Has it not been proved that animals are not unworthy of the regard of Him who reigns enthroned in the highest heavens? Shall they be deemed beneath the regard of those whose duty it is to enforce the laws of heaven’s great King; or shall an apology be ever thought necessary for advocating, in the house of God, and cause in which the interest of humanity are even remotely concerned? Would that the subject had been more frequently the theme of pulpit exhortation! Would the clergy of all denominations had sometimes selected this useful topic for discussion, instead of those metaphysical questions of theology which are as unprofitable as they are abstruse.…They could do much more than any legislature for the correction of inhumanity. (57)

Human laws may reach and punish a few of the most atrocious acts of cruelty which are exposed to observation; but there are thousands and tens of thousands of such acts that escape their cognizance and defy their authority. To find a remedy for the evil, we must go to a higher source. We must appeal to the law of God. We must address the moral principles. We must bring the feelings of benevolence to operate on the conduct. We must instil the dews of compassion into the bosoms of our children. Humanity must elevate her voice and inculcate her precepts in the nursery—in the school—in the college—in the lecture-room—in the courts of justice—and the pulpit. She must speak aloud with a hundred tongues by the mouths of orators and poets, philosophers and divines, by mothers to their daughters, and by fathers to their sons, and by masters and mistresses to their male and female servants. She must invoke the gentlemen of the press to stamp her dictates in the indelible characters of ink and type, and give them a passport to the extremities of the world. She must implore them to brand, with a disreputable stigma, every cruel deed. Those who are not to be allured to mercy by high and generous motives, may be deterred from cruelty by the dread of shame. (57-8)

Humanity must elevate her voice and inculcate her precepts in the nursery—in the school—in the college—in the lecture-room—in the courts of justice—and the pulpit. She must speak aloud with a hundred tongues by the mouths of orators and poets, philosophers and divines, by mothers to their daughters, by fathers to their sons, and by masters and mistresses to their male and female servants. She must invoke the gentlemen of the press to stamp her dictates in the indelible characters of ink and type, and give them a passport to the extremities of the world. She must implore them to brand, with a disreputable stigma, every cruel deed. (58)

Some parents may deem it a matter of small consequence how their children are allowed to indulge a disposition to be cruel. They may consider the life of an insect or a bird as a thing of no value, and care not how dogs are lashed, cats hunted, and flies impaled. But these trifles, if such they seem, may lead to serious, and even appalling results; for all evil is progressive, and a little leaven leaveneth the whole lump. While a child is permitted to torture a poor animal, he is in training to become an executioner. His senses grow familiar with sufferings. The voice of nature is stifled in his heart. To a mind of common sensibility, the pain of another creature seems to communicate itself by some sympathetic tie: in him it will at length cease to excite any emotion but pleasure. The noise of the scourge and the clank of the chain are as music to his ear. He becomes the terror of his trembling domestics, a stern father, a savage husband, a tyrannical master. (58)

Ye, then, who study the good of your children, and wish to behold them amiable and virtuous, beware how you indulge in them the least propensity to be cruel; for every such propensity tends directly to destroy the best principles of our nature. Charge them, as they fear your displeasure, never to subject a creature in their power to one moment’s unnecessary pain. If they cannot feel, from defect of natural sensibility, they can, at least, be brought to act from a sense of duty. The head may prove a kind auxiliary to the heart. Convince them that other creatures are as sensible of harsh treatment as themselves, and that to abuse them is to abuse the power which the Author of all has bestowed. Again, ask them seriously and affectionately how they would like to share the lot of those creatures whose slavery is embittered by the rigid and capricious treatment of their keepers. Make them ashamed of injuring defenceless animals which have no mode of appealing to justice, or seeking redress for their wrongs. Join pious reflections to your admonitions. Tell them, on the authority of Holy Writ, that God regards the life of a sparrow—that the meanest reptile which creeps in the dust, or insect that sports in the breeze, is not beneath his care, but that he beholds and provides for them all, and will not suffer them to be injured with impunity. By such a plan, if you persevere, you can scarcely fail to produce the intended effect. (58-9)

Ask them seriously and affectionately how they would like to share the lot of those creatures whose slavery is embittered by the rigid and capricious treatment of their keepers. Make them ashamed of injuring defenceless animals which have no mode of appealing to justice, or seeking redress for their wrongs. (59)

Biography-Commentary-Excerpts-Reviews

「1830」Voice of Humanity: “We hail with the warmest satisfaction the appearance of this most masterly discourse. A spirit of the purest and sublimest benevolence breathes in every page, emanating from an exhaulted mind, capable of truly appreciating the rank of man in this lower world, as God’s vicegerent, to emulate the attributes of his Creator, and diffuse joy and happiness. Dr. Drummond has not laid on the shrine of humanity an offering which has cost him nothing. The discourse is not common-place, but is enhanced in value, by extensive research, true originality of thought, and beauty of language. To such merits is superadded, in an Appendix, the most valuable and choice collection of notes we have ever seen in any work; from which we purpose, from time to time, to enrich our pages.”—Voice of Humanity 1 (1830-Nov) 55-61; Google Books: ONine Library of Free eBooks.

「1868」 Howard Malcom, “Cruelty to Brutes,” in References to the Principal Works in Every Department of Religious Literature (Boston, 1868).