John Oswald

The Cry of Nautres, or an Appealto Mercy and Justice on Behalf of the Perscuted Animals

「1791」 John Oswald, The Cry of Nature, or an Appeal to Mercy and to Justice, on Behalf of the Persecuted Animals (London, 1791; Online at Animal Rights History, 2006).

And ye, when he considers the natural bias of the human heart to the side of mercy, and observes on all hands the barbarous governments of Europe giving way to a better system of thing, he is inclined to hope that the day is beginning to approach when the growing sentiment of peace and good-will towards men will also embrace, in a wide circle of benevolence, the lower orders of life.

Sovereign despot of the world, lord of the life and death of every creature,—man, with the slaves of his tyranny, disclaims the ties of kindred. Howe’er attuned to the feelings of the human heart, their affections are the mere result of mechanic impulse; howe’er they may verge on human wisdom, their actions have only the semblance of sagacity: enlightened by the ray of reason, man is immensely removed from animals who have only instinct for their guide, and born to mortality, he scorns with the brutes that perish, a social bond to acknowledge. Such are the unfeeling dogmas, which, early instilled into the mind, induce a callous insensibility, foreign to the native texture of the heart; such the cruel speculations which prepare us for the practice of that remorseless tyranny, and which palliate the foul oppression that, over inferior but fellow-creatures we delight to exercise.

The dumb creatures, say they, were sent by God into the world, to exercise our charity; and, by calling forth our affections, to contribute to our happiness. We consider them as mute brethren, whose wants it becomes us to interpret, whose defects it is our duty to supply. The benevolence which on them we bestow, is amply repaid by the benefits which they bring; and the pleasing return for our kindness is, that endearing gratitude which renders the care of providing for them rather a pleasing occupation than a painful task.

And innocently mayest thou indulge the desires which Nature so potently provokes; for see ! the trees are overcharged with fruit; the bending branches seem to supplicate for relief; the mature orange, the ripe apple, the mellow peach invoke thee, as it were, to save them from falling to the ground, from dropping into corruption. They will smile in thy hand; and, blooming as the rosy witchcraft of thy bride, they will sue thee to press them to thy lips; in thy mouth they will melt not inferior to the famed ambrosia of the gods.

But of animals far other is the fare: for, alas ! when they from the tree of life are pluck’d, sudden shrink to the chilly hand of death the withered blossoms of their beauty; quenched in his cold cold grasp expires the lamp of their loveliness ; and, struck by the livid blast of putrefaction loathed, their every comely limb in ghastly horror is involved.

On the carcase we feed, without remorse, because the dying struggles of the butchered creature are secluded from our sight; because his cries pierce not our ear; because his agonizing shrieks sink not into our soul: but were we forced, with our own hands, to assassinate the animals whom we devour, who is there amongst us that would not throw down, with detestation, the knife; and, rather than embrue his hands in the murder of the lamb, consent, for ever, to forego the favorite repast?

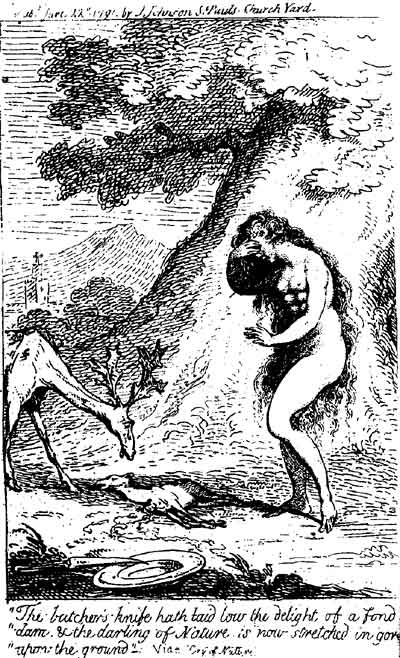

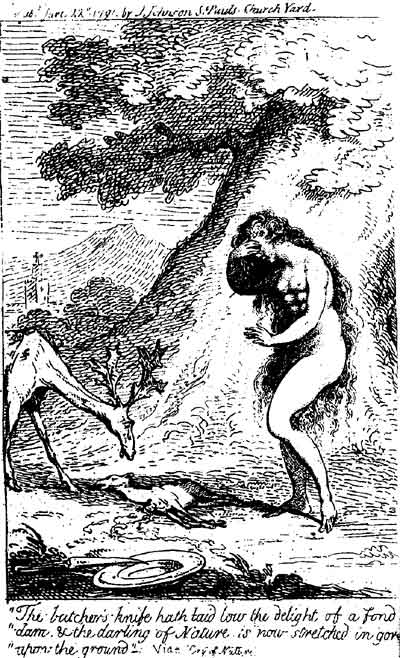

But come, ye men of scientific subtlity, approach and examine with attention this dead body. It was late a playful fawn, which, skipping and bounding on the bosom of parent earth, awoke, in the soul of the feeling observer, a thousand tender emotions. But the butcher’s knife hath laid low the delight of a fond dam, and the darling of nature is now stretched in gore upon the ground. Approach, I say, ye men of scientific subtlity, and tell me, tell me, does this ghastly spectacle whet your appetite? Delights your eyes the sight of blood? Is the steam of gore grateful to your nostrils, or pleasing to the touch, the icy ribs of death ? But why turn ye with abhorrence? Do you then yield to the combined evidence of your senses, to the testimony of conscience and common sense; or with a species of rhetoric, pitiful as it is perverse, will you still persist in your endeavour to persuade us, that to murder and innocent animal, is not cruel nor unjust; and that to feed upon a corpse, is neither filthy nor unfit?

Good God! Is it so heinous an offence against society, to respect in other animals that principle of life which they have received, no less than man himself, at the hand of Nature? O, mother of every living thing! O, thou eternal fountain of beneficence; shall I then be persecuted as a monster, for having listened to thy sacred voice? to that voice of mercy which speaks from the bottom of my heart; while other men, with impunity, torment and massacre the unoffending animals, while they fill the air with the cries of innocence, and deluge thy maternal bosom with the blood of the most amiable of thy creatures!

THE

CRY OF NATURE;

OR,

AN APPEAL

TO

MERCY AND TO JUSTICE,

ON BEHALF OF THE

PERSECUTED ANIMALS.

BY JOHN OSWALD,

MEMBER OF THE CLUB DES JACOBINES.

_________ Mollissima corda

Humano generi dare se natura satetur

Quæ lacrymas dedit: hæe nostri pars optima sensus.

JUVENAL, Sat. XV. ver. 131.

___________

LONDON;

PRINTED FOR,J. JOHNSON, NO 72, ST. PAUL’S

CHURCH-YARD. 1791.

ADVERTISEMENT.

FATIGUED with answering the enquiries, and replying to the objections of his friends, with respect to the singularity of his mode of lie, the Author of this performance conceived that he might consult his ease by making, once fro all, a public apology for his opinions. Those who despise the weakness of his arguments will nevertheless learn to admit the innocence of this tenets, and suffer him to pursue, without molestation, a system of life that is more the result of sentiment than of reason, in a man who imagines that the human race were not made to live scientifically, but according to nature.

The Author is very far from entertaining a presumption that his slender labours (crude and imperfect as they are now hurried to the press) will ever operate an effect on the public mind—「ii」 And ye, when he considers the natural bias of the human heart to the side of mercy, and observes on all hands the barbarous governments of Europe giving way to a better system of things, he is inclined to hope that the day is beginning to approach when the growing sentiment of peace and good-will towards men will also embrace, in a wide circle of benevolence, the lower orders of life.

At all events, the pleasing persuasion that his work may have contributed to mitigate the ferocities of prejudice, and to diminish in some degree the great mass of misery which oppresses the animal world, will in the hour of distress convey to the Author’s heart a consolation which the toot of calumny will not be able to impoison.

The

CRY OF NATURE, &c.

DID we rightly understand the principles, and the true scope of Hindoo religion and legislation, which are established on the same basis, we should find that, to the gratitude and admiration of the human race, few legislators can exhibit so just a claim as the lawgiver of Hindostan. Of this 「2」 we shall soon become sensible, if we compare him, not with those bold pretenders to inspiration, better known by the mischiefs which they have brought upon the human race, than by the wisdom of their laws; and whose names ought to sound as odious in our ears as their dreary dogmas have been pernicious to the world—but with those genuine legislators who have adopted, as the basis of legislation, the dictates of philosophy and good sense.

「3」 But there is one article which distinguishes, from all others, the doctrine of Burmah, and which raises, above all religions on the face of the earth, the sacred system of Hindostan. Satisfied with extending to man alone the moral scheme, the best and mildest of other modes of worship, to the cruelty and caprice of the human race, every other species of animal have unfeelingly abandoned. Sovereign despot of the world, lord of the life and death of every creature,—man, with the slaves of his 「4」tyranny, disclaims the ties of kindred. Howe’er attuned to the feelings of the human heart, their affections are the mere result of mechanic impulse; howe’er they may verge on human wisdom, their actions have only the semblance of sagacity: enlightened by the ray of reason, man is immensely removed from animals who have only instinct for their guide, and born to mortality, he scorns with the brutes that perish, a social bond to acknowledge (1). Such are the unfeeling dogmas, which, 「5」 early instilled into the mind, induce a callous insensibility, foreign to the native texture of the heart; such the cruel speculations which prepare us for the practice of that remorseless tyranny, and which palliate the foul oppression that, over inferior but fellow-creatures we delight to exercise.

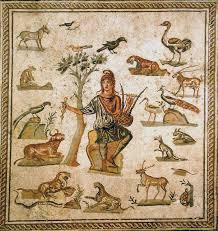

Far other are the sentiments of the merciful Hindoo. Diffusing over every order of life his affections, he beholds, in every creature, a kinsman: he rejoices in the 「6」 welfare of every animal, and compassionates his pains; for he knows, and is convinced, that of all creatures the essence is the same, and that one eternal first cause is the father of us all (2). Hence more solicitous to save than the cruel vanity and exquisite voraciousness of other nations are ingenious to discover in the bulk, or taste, or beauty of every creature, a cause of death, an incentive to murder, the merciful mythology of Hindostan hath consecrated, by the metamorphosis of the Deity, every 「7」 species of animal. A Christnah, a Lechemi, a Madu assuming, in the course of their eternal metempsychosis, the form of a cow, a lizard, or a monkey, sanctify and render inviolate the persons of those animals; and thus, with the sentiments of pity, concur the prejudices of religion, to protect the mute creation from those injuries which the powerful are but too prone to inflict upon the weak.

「8」 When they converse, however, with those of a different religion, the Hindoos justify by arguments; independent of mythology, their humane conduct towards the inferior orders of animals. The dumb creatures, say they, were sent by God into the world, to exercise our charity; and, by calling forth our affections, to contribute to our happiness. We consider them as mute brethren, whose wants it becomes us to interpret, whose defects it is our duty to supply. The benevolence「9」 which on them we bestow, is amply repaid by the benefits which they bring; and the pleasing return for our kindness is, that endearing gratitude which renders the care of providing for them rather a pleasing occupation than a painful task.

From our tables turns with abhorrence the tender-hearted Hindoo. To him our feasts are the nefarious repasts of Polyphemus; while we contemplate, with surprise, his absurd clemency, and 「10」 regard his superstitious mercy as an object of merriment and contempt. And yet in spite of that insensibility with which the practice of oppression, and the habits of speculative cruelty, have incased our feelings, still are we affected by the sufferings of other animals; and from their distress are drawn the finest images of sorrow. Would the poet paint the deep despair of the maid, from whose side the ruthless hand of death hath snatched sudden the lord of her affections, the love of「11」 her virgin heart; what simile more apt to excite the sympathetic tear, than the turtle-dove forlorn, who mourns, with never-ceasing wail, her murdered mate? Who can refuse a sigh to the sadly-pleasing strains of Philomela?

When returning with her loaded bill,

Th’ astonished mother finds a vacant nest,

By the hard hand of unrelenting clowns,

Robb’d: to the ground the vain provision falls;

Her pinions ruffle, and low-drooping, scarce

Can beat the mourner to the poplar shade,

Where, all abandon’d to despair, she sings

「12」 Her sorrows through the night, and on the boughs

Sole sitting; still, at every dying fall,

Takes up again her lamentable strain

Of winding woe, till, wide around the woods,

Sigh to her song, and with her wail resound.

But here the sons of science sport with the sentiments of mercy; and why, with a malicious grin, demands the modern sophist, why then is man furnished with the canine, or dog-teeth, except that nature meant him carnivorous?—Fallacious argument! Is the fitness of an action to be determined 「13」 purely by the physical capacity of the agent? Because nature, kindly provident, has bestowed upon us a superabundance of animal vigour, does it follow that we ought to abuse, by habitual exertions, and excess of force, evidently granted to guard our existence on occasions of fire distress? In cases of extreme famine we destroy and devour each other; but from thence will any one pretend to prove, that man was made to feed upon his fellow men?

「14「 Most unfortunately too for this canine argument of those advocates of murder, it happens, that the monkey, and especially the man-monkey, who subsistssolelyon fruit, is furnished with teeth as canine, as keenly pointed, as those of man (3).

Having thus briefly refuted an objection, which modern wisdom has deemed insuperable, I proceed barely to point out a few reason, which seem to indicate, that man was intended by nature, or, in 「15」 other words, by the disposition of things, and the physical fitness of his constitution, to live entirely on the produce of the earth.

In the first place, growing spontaneous in every clime, the fruits of the earth are easily attained, while animal food is a luxury, which the major part of mankind cannot reach. The peasantry of Turkey, France, Spain, Germany, and even of England, that most carnivorous of all countries, can seldom afford to eat flesh. The「16」 barbarous tribes of North-America, who subsist almost entirely by hunting, can scarce find, in a vast extent of country, a scanty subsistence for a handful of inhabitants.

The practice of agriculture softens the human heart, and promotes the love of peace, of justice, and of nature.

The exercise of hunting, on the contrary, irritate the baneful passions of the soul; her vagabond votaries delight in blood, in rapine,「17」 and devastation. From the wandering tribes of Tartars, the demons of massacre and havoc have selected their Tamerlanes and their Attilas, and have poured forth their swarms of barbarians to desolate the earth.

Animal food overpowers the faculties of the stomach, clogs the functions of the soul, and renders the mind material and gross. In the difficult, the unnatural task of converting into living juice the cadaverous oppression, a great dea 「18」 of time is consumed, a great deal of danger is incurred (4). Far other are the pure repasts of rural Pan, far other the kindly nouriture which the living herbs afford:

The living herbs that spring profusely wild

O’er all the deep-green earth, beyond the power

Of botanist to number up their tribes:

But how their virtues can declare, who pierce,

With vision pure, into those secret stores

Of health, and life, and joy, the food of man,

While yet he lived in innocence, and told

「19」 A length of golden years unflesh’d in blood,

A stranger to the savage arts of life,

Death, rapine, carnage, surfeit and disease;

The lord and not the tyrant of the world.

To this primitive diet health invites her votaries. From the produce of the field her various banquet is composed: hence she dispenses health of body, hilarity of mind, and joins to animal vivacity the exalted taste of intellectual life. Nor is Pleasure, handmaid of Health, a stranger to the feast. Thither the bland Divinity conducts 「20」 the captivated senses; and by their predilection for the pure repast, the deep-implanted purpose of nature is declared.

By sweet but irresistible violence, vegetation allures our every sense, and plays upon the sensorium with a sort of blandishment, which at once flatters and satisfies the soul. To they eye, seems aught more beauteous than this green carpet of nature, infinitely diversified as it is by pleasing interchange of lovely tints? What 「21」 more grateful to the smell, more stimulous of appetite, than this collected fragrance that flows from a world of various perfumes? Can art, can the most exquisite art equal the native flavours of Pomona; or worthy to vie with the spontaneous nectar of nature, are those sordid sauces of multiplex materials, which the ministers of luxury compose to irritate the palate and to poison the constitution? 「22」 And innocently mayest thou indulge the desires which Nature so potently provokes; for see ! the trees are overcharged with fruit; the bending branches seem to supplicate for relief; the mature orange, the ripe apples, the mellow peach invoke thee, as it were, to save them from falling to the ground, from dropping into corruption. They will smile in thy hand; and, blooming as the rosy witchcraft of thy bride, they will sue thee to press them to thy lips; in thy mouth they will melt not 「23」 inferior to the famed ambrosia of the gods.

But of animals far other is the fare; for, alas ! when they from the tree of life are pluck’d, sudden shrink to the chilly hand of death the withered blossoms of their beauty; quenched in his cold cold grasp expires the lamp of their loveliness; and, struck by the livid blast of putrefaction loathed, their every comely limb in ghastly horror is involved. And shall we leave the ling herbs to seek, in 「24」 the den of death, an obscene aliment?—Insensible to the blooming beauties of Pomona, unallured by the fragrant fume that exhales from her groves of golden fruits, undetained by the nectar of nature, by the ambrosia of innocence undetained, shall the voracious vultures of our impure appetite speed across the lovely scenes of rural Pan, and alight in the loathsome sink of putrefaction to devour the funeral of other creatures, to load, with cadaverous rottenness, a wretched stomach?

「25」 And is not the human race itself highly interested to prevent the habit of spilling blood? For will the man, habituated to havock, be nice to distinguish the vital tide of a quadruped, from that which flows from a creature with two legs? Are the dying struggles of a lambkin less affecting then the agonies of any animal whatever? Or will the ruffian, who beholds, unmoved, the supplicating looks of innocence itself, and, reckless of the calf’s infantine cries, plunges, pitiless, in her「26」 quivering side, the murdering steel; will he turn, I say, with horror from human assassination?

What more advance can mortals make in sin,

So near perfection, who with blood begin? Deaf to the calf that lies beneath the knife

Looks up, and from the Butcher begs her life;

Deaf to the harmless kid that, ere he dies

All methods to procure thy mercy tries;

And imitates, in vain, thy Children’s cries—

Where will he stop?

DRYDEN’s Ovid.

「27」 From the practice of slaughtering an innocent animal, to the murder of man himself, the steps are neither many nor remote. This our forefathers perfectly understood, who ordained that, in a cause of blood, no butcher, nor surgeon, should be permitted to sit in jury.

Animals, whom we have once learnt to destroy, without remorse, we are easily brought, without scruple, to devour. The corpse 「28」 of a man differs in nothing from the corpse of any other anima; and he who finds the last palatable, may, without much difficulty, accustom his stomach to the first. To cannibalism carnivorous nations have not unseldom been addicted (5). The antient Germans sometimes rioted in human repasts; and, on the bodies of their enemies, fees, with infernal satisfaction, the native tribes of America.

「29」 But from the texture of the very human heart arises the strongest argument in behalf of the persecuted creatures. Within us there exists a rooted repugnance to the spilling of blood; a repugnance which yields only to custom, and which even the most inveterate custom can never entirely overcome. Hence the ungracious task of shedding the tide of life, for the gluttony of our table, has, in every country, been committed to the lowest class of men; and their profession is, in every country, 「30」an object of abhorrence. On the carcase we feed, without remorse, because the dying struggles of the butchered creature are secluded from our sight; because his cries pierce not our ear; because his agonizing shrieks sink not into our soul: but were we forced, with our own hands, to assassinate the animals whom we devour, who is there amongst us that would not throw down, with detestation, the knife; and, rather than embrue his hands in the murder of the lamb, consent, for 「31」ever, to forego the favorite repast? What then shall we say? Vainly planted in our breast, is this abhorrence of cruelty, this sympathetic affection for every animal? Or, to the purpose of nature, do the feelings of the heart point more unerringly than all the elaborate subtilty of asset of men, who, at the shrine of science, have sacrificed the dearest sentiments of humanity?

Ye sons of moderns science, who court not wisdom in her walks of 「32」 silent meditation in the grove, who behold her not in the living loveliness of her works, but expect to meet her in the midst of obscenity and corruption; ye who dig for knowledge in the depth of the dunghill, and who hope to discover wisdom enthroned amid the fragments of mortality, and the abhorrence of the senses; ye that with ruffian violence interrogate trembling nature, who plunge into her maternal bosom the butcher knife, and, in quest of your nefarious science, the fibres of agonizing 「33」 animals, delight to scrutinize; ye dare also to violate the human form august; and, holding up the entrails of man, ye exclaim; behold the bowels of a carnivorous animal (6) !—Barbarians ! to these very bowels I appeal against your cruel dogmas; to these bowels, fraught with mercy, and entwined with compassion; to these bowels which nature hath sanctified to the sentiments of pity and of gratitude; to the yearnings of kindred, to the melting tenderness of love !

「34」Had nature intended man an animal of prey, would she in his breast have implanted an instinct so adverse to her purpose? Could she mean that the human race should eat their food with compunction and regret: that every morsel should be purchased with a pang, and every meal of man impoisoned with remorse? Would Nature, with the milk of kindness, have filled a bosom which unfeeling ferocity should inflame? Would she not rather, in order to enable him to brave the piercing cries of 「35」anguish, have wrapt, in his ribs of brass, his ruthless heart; and, with iron entrails, have armed him to grind, without remorse, the palpitating limbs of agonizing life? But has Nature wing’d, with fleetness, the sect of man, to overtake the flying prey? and where are his fangs to tear asunder the creatures destined for his food? Glares in his eye-ball the lust of carnage? Does he scent afar the footsteps of his victim? Does his soul pant for the feastof blood? Is the bosom of man「36」the rugged abode of bloody thoughts; and from their den of death rush forth, at sight of other animals, his rapacious desires to slay, to mangle, to devour?

But come, ye men of scientific subtilty, approach and examine with attention this dead body. It was late a playful fawn, which, skipping and bounding on the bosom of parent earth, awoke, in the soul of the feeling observer, a thousand tender emotions. But the butcher’s knife hath laid low the delight 「37」 of a fond dam, and the darling of nature is now stretched in gore upon the ground. Approach, I say, ye men of scientific subtilty, and tell me, tell me, does this ghastly spectacle whet your appetite? Delights your eyes the sight of blood? Is the steam of gore grateful to your nostrils, or pleasing to the touch, the icy ribs of death? But why turn ye with abhorrence? Do you then yield to the combined evidence of your senses, to the testimony of conscience and common sense; or 「38」 with a species of rhetoric, pitiful as it is perverse, will you still persist in your endeavour to persuade us, that to murder and innocent animal, is not cruel nor unjust; and that to feed upon a corpse, is neither filthy nor unfit?

O that man would interrogate his own heart ! O that he would listen to the voice of nature ! For powerfully she stirs within us; and, from the very bottom of the human heart, with moving voice she pleads. Why, she cries, 「39」 oh ! why shouldst thou dip thy hand in the blood of thy fellow-creatures without cause? Have I not amply, not only for the wants, but even for the pleasures of the human race, provided? Prodigal of blessings, pour I not forth for man an abundant banquet; a banquet, in which the salubrious and savoury, the nourishing and palatable, are blended in proportions infinitely various? And, while lavish of my gifts, thy lap I load with the produce of the seasons as they pass; while to thy 「40」 lips I press the purple juice of joy, while thou riotest, in fine, in excess of enjoyment; dost thou still thirst, insatiate wretch ! for the blood of this innocent little lamb, whose sole food is the grass on which he treads; his only beverage the brook that trickles muddy from his feet? Alas ! let my tears— alas ! for a poor innocent that hath done thee no harm, which, indeed, is incapable of harm, let the tears of nature plead ! Spare, spare, I beseech thee by every tender idea; spare my maternal bosom the unutterable 「41」 anguish which there the cries of agonizing innocence excite, whether the creature that suffers be a lambkin or a man. See the little victim how he wantons unconscious of coming fate; unsuspicious of harm, the up-lifted steel he views, innocent and engaging as the babe, that presses, playful, the bosom of her, in whom thy bliss is complete. Why shouldst thou kill him in the novelty of life; why ravish him from the sweet aspect of the sun, while yet, with fresh delight, he admire 「42」 the blooming face of things; while, to the pipe of the shepherd, leaps with joy his light heart; and, unblunted by enjoyment, his virgin senses sweetly vibrate to the bland touch of juvenile desire ! And why, oh ! why shouldst thou kill him in the novelty of life ! Alas ! she will seek him in vain; alas, his afflicted dam will seek him through all his wonted haunts ! Her moans will move to compassion the echoing dell: her cries will melt the very rocks !—But who, on the obduracy of the human heart, 「43」shall pour, O, nature, thy melting voice? The secret sources of the soul, what master hand shall unlock and bid the heart again to flow through long-forgotten channels of compassions!

Alas, the very attempt could not fail to encounter the ridicule of the mob, the obloquy of the sensual, and the sneers of the unfeeling. The advocate of mercy would incur the reproach of misanthropy, and be traduced as a wild unsocial animal, who had formed a nefarious design to curtai「44」 the comforts of human life (7),— Good God! Is it so heinous an offence against society, to respect in other animals that principle of life which they have received, no less than man himself, at the hand of Nature? O, mother of every living thing! O, thou eternal fountain of beneficence; shall I then be persecuted as a monster, for having listened to thy sacred voice? to that voice of mercy which speaks from the bottom of my heart; while other men, with impunity, torment and massacre 「45」 the unoffending animals, while they fill the air with the cries of innocence, and deluge thy maternal bosom with the blood of the most amiable of thy creatures!

And yet those channels of sympathy for inferior animals, a long, a very long disuse has not been able, altogether, to choak up. Even now, notwithstanding the narrow, joyless, and heard-hearted tendency of the prevailing superstitions; even now, we discover, in every corner of the globe, some good-natured prejudice in 「46」 behalf of the persecuted creatures: we perceive, in every country, certain privileged animals, whom even the ruthless jaws of gluttony dare not to invade. For to pass over unnoticed the vast empires of India, Thibet, and China, where the lower orders of life are considered as relative parts of society, and are protected by the laws and religion of the natives, the Tartars abstain from several kinds of animals: the Turks are charitable to the very dog, whom they abominate; and even the English peasant pays towards the Robin-red-breast「47」 an inviolate respect to the rights of hospitality:

____________one alone,

The red-breast, sacred to the household-gods,

Wisely regardful of the embroiling sky,

In joyless fields, and thorny thickets, leaves

His shivering mates, and pays to trusted man

His annual visit.

Long after the perverse practice of devouring the flesh of animals had grown into inveteratehabit among the people, there existed 「48」 still, in almost every country, and of every religion, and of every sect of philosophy, a wiser, a purer, and more holy class of men, who preserved, by their institutions, by their percepts, and their example, the memory of primitive innocence and simplicity. The Pythagoreans abhorred the slaughter of animals: Epicurus, and the worthiest part of his disciples, bounded their delights with the produce of their garden: and of the primitive Christians, several sects abominated the feast of blood, and were satisfied with the 「49」 food which nature, unviolated, brings forth for our support (8).

But feeble amongst nations, barbarous or civilized, this principle of sympathy and compassion operates in the breast of the savage with a force almost incredible. No less compassionate to their cattle than the Hindoos, whom, in most of their opinions and customs, they resembled, were the Aborigenes of the Canary of Happy Islands (happy, indeed, if innocence and happiness be the same !) If their「50」 parched fields demanded the refreshing dew of heaven; or, if deluged with rain, they required the drying ardour of the sun, the simple Guanchos conducted their cattle to a place appointed, and severing the young ones from their dams, they raised a general bleating in the flock, whose cries, they believed, had power to move the ALMIGHTY GOOD to hear their supplication, and to grant their request (9). And who, with a beneficent being to intercede, so fit as those innocent animals? To 「51」a God of love, how much more acceptable the prayers of the humane Guanchos, mingled with the plaintive cries of their guileless mediators; How much more moving, I say, their innocent supplication, than the ruffian petitions of those execrable Arabs, who, imploring mercy, perpetrated murder, and embrued in the blood of agonizing innocence, their hands holding up, dared to beseech thy compassion, thou common father of all that breathe the breath of live !

「52」 The vestiges of that amiable sympathy which, even in this degenerate age are still visible, strongly indicate the cordial harmony which, in the age of innocence, subsisted between man and the lower orders of life.

Man, in a state of nature, is no, apparently, much superior to other animals. His organization is, no doubt, extremely happy; but then the dexterity of his figure is counterpoised by great advantages in other creatures. Inferior to the「53」 bull in force; and in fleetness to the hound; the os sublime, or front erect, a feature which he bears in common with the monkey, could scarcely have inspired him with those haughty and magnificent ideas, which the pride of human refinement thence endeavours to deduce (10). Exposed, like his fellow-creatures, to the injuries of the air; urged to action by the same physical necessities; susceptible of the same impressions; actuated by the same passions; and, equally subject to the pains of 「54」 disease, and to the pangs of dissolution, the simple savage never dreamt that his nature was so much more noble, or that he drew his origin from a purer source, or more remote than the animals in whom he saw resemblance so compleat. Nor were the simple sounds, by which he expressed the singleness of his heart, at all fitted to flatter him into that fond sense of superiority over the creatures, whom the fastidious insolence of cultivated ages absurdly styles mute. I say, absurdly styles 「55」 mute; for with what propriety can that name be applied, for example, to the little syrens of the grove, to whom nature has granted the strains of ravishment, the soul of song? those charming warblers who pour forth, with a moving melody which human ingenuity vies with in vain, their loves, their anxiety, their woes. In the ardour and delicacy of his amorous expressions, can the most impassioned, the most respectful lover the glossy kind surpass, as described 「56」by the most beautiful of all our poets.

________________the glossy kind

Try every winning way inventive love

Can dictate; and, in courtship to their mates,

Pour forth their little souls. First wide around,

With distant awe, in airy rings they rove,

Endeavouring, by a thousand tricks, to catch

The cunning, conscious, half-averted glance

Of their regardless charmer. Should she seem

Soft’ning, the least approvance to bestow,

「57」 The brisk advance; then, on a sudden struck

Retire disorder’d; then again approach,

In fond rotation spread the spotted wing

And shiver every feather with desire.

And, indeed, has not nature given, to almost every creature, the same spontaneous signs of the various affections? Admire we not in other animals whatever is most eloquent in man, the tremor of desire, the tear of distress (11), the piercing cry of anguish, the pity-pleading look, expressions that speak the soul with a feeling 「58」 which words are feeble to convey (12)?

From likeness mutual love proceeded; and mutual love, in the bonds of society with man, the milder and more congenial animals united. Amply repaid by the fleecy warmth of the lamb, by the rich, the salubrious libations of the cow, was that protection which the fostering care of the human race afforded to the cattle of the field. Sometimes too, a tie still more tender, cemented the friendship 「59」 between man and other animals. Infants, in the earlier ages of the world, to the teats of the tenants of the field were not unseldom submitted. Towards the goat that gave him suck, the fond boy, the throb of filial gratitude has felt: and, for the children of men, have yearned, with tenderness maternal, the bowels of the ewe (13). Educated together, they were endeared to each other by mutual benefits; a fond, a lively friendship, was the consequence of their union (14). Never by primæval 「60」 man, were violated the rights of hospitality; never, in his innocent bosom, arose the murderous meditation; never, against the life of his guests, his friends, his benefactors, did he the butcher-axe uplift. Sufficient were the fruits of the earth for his subsistence; and, satisfied with the milk of her maternal bosom, he sought not, like a perverse child, to spill the blood of nature.

But not to the animal world alone were the affections of man 「61」 confined: for whether the glowing vault of heaven he surveyed, or his eyes reposed on the greeny freshness of the lawn; whether to the tinkling murmur of the brook he listened, or in pleasing melancholy melted amid the gloom of the grove, joy, rapture, veneration filled his guileless breast: his affections showed on every thing around him; his soul around every tree or shrub entwined, whether they afforded him subsistence or shade (15): and wherever his eyes wandered, wondering he beheld 「62」 his gods, for his benefactors smiled on every side, and gratitude gushed upon his bosom whatever object met his view (16).

_____o lovely seem’d

The landscape ! _____

_____and to the heart inspires

Vernal delight and joy,_____

But what were the beauties of the landscape to the living roses that bloomed on the cheeks of his love ! And what were the vernal delights compared to the soft thrill of transport which the kind glance「63」 of his beloved excited his soul ! From that joyous commotion of his heart arose the Queen of young desire; on the fond fluctuation of his bosom glided the new-born VENUS, deckt in all her glowing potency of charms. And thou too, O CUPID, O CUPID, or if RAMA-DEVA more delight thine ear; art thou not also with all they GRACES a glad emanation of primal bliss?—But as yet the Demon of Avarice had not poisoned the source of joy; they darts, O LOVE, were not barbed with despair; but「64」 thy arrow were the trill of rapture, they only pain the blissful anguish of enjoyment !

Such were the feasts of primæval innocence; such the felicity of the golden age. But long since, alas ! are those happy days elapsed. That they ever did exist is a doubt with the depravity of the present day; and so unlike our actual state of misery, the story of primal bliss is numbered with the dreams of visionary bards.「65」 But that such a state did exist, the concording voice of various tradition offers a convincing proof; and the lust of knowledge is the fatal cause, to which the indigenous tale, of every country, attributes the loss of paradise and the fall of man (18). ‘Twas this dire curiosity that prompted Pandora to pry into the fatal box ! this was the subtle serpent which prevailed on Eve to taste the tree of knowledge, and hence, from the fields of innocence, were expelled the human race, in consequence 「66」 of eating the forbidden fruit; or, in other words, misled by the ignis fatuus of science, man forsook the sylvan gods, and abandoned the unsollicitous, innocent, and noble simplicity of the savage, to embrace the anxious, operose, mean, miserable, and ludicrous life of man civilized (19). Hence the establishment of towns and cities, those impure sources of misery and vice; hence arose prisons, palaces, pyramids, and all those other amazing monuments of human slavery; hence the unequality 「67」 of ranks, the wasteful wallow of wealth, and the meagerness of want, the abject front of poverty, the insolence of power; hence the cruel superstitions which animate, to mutual massacre, the human race; and hence, impelled by perverse ambition and insatiate thirst of gain, we break through all the barriers of nature, and court, in very corner of the globe, supremacy of guilt.

The arts, as those pernicious inventions were entitled, in one 「68」 common ruin, involved with man the inferior orders of animals. But to this atrocious tyranny which over kindred souls we now exercise without feeling or remorse, the human race were conducted by gradual abuse. For however severe the services might be which man, newly enlightened, require from his former friends, still he respected their live, and, satisfied with their labour, abhorred to shed their blood (20). 「69」The last tie of sympathy was severed by superstition. The general harmony of this stupendous whole is at times disturbed by partial disorder; the beautiful system of things which manifests the beneficence of nature, is sometimes marred by fearful accidents that are apt on the mind of man to impress and idea of supernatural malevolence. Aghast, trembling before the angry Gods, he made haste his soul to redeem by the blood of other creatures, and the sanguinary cravings of immortal 「70」 appetite were fated by the smoke of butchered sheep, and the steam of burnt offerings (21). The horror of those infernal rites insensibly wore off; frequent oblations allured the curious cupidity of man, and the human race were imperceptible seduced to share the sanguinary feast, which superstition had spread fro the principle of ill. Bolder than the rest, and more habituated to the sight of blood, the priest, who was the butcher of the victims, which he offered to supernatural malevolence, 「71」 dared solemnly in the name, and by the authority of the Gods whom he served, to affirm that heaven to man had granted every animal for food (22). So flattering to the perverse lust of his hearers, the impious lie was greedily received, and swallowed with unscrupulous credulity. Still, however, with diffidence was the deed perpetrated: not without many august ceremonies was the murder executed by the ministers of the Gods; the deities were solemnly invoked to sanctify by 「72」 their presence a deed which their example had provoked; and the victim was led to slaughter like a distinguished criminal of state, whose life is sacrificed not so much to atone to the violated laws of society, as to gratify the caprice, or to promote the perverse ambition of a tyrant. Yet even the venerable veil of religion, which covers a multitude of sins, could hardly hide the horror of the act. But the pains that were taken to trick the animal into a seeming 「73」 consent to his destruction, the injustice of the deed was clearly acknowledged; nay, it was even necessary that he should offer himself as it were voluntary victim, that he should advance without reluctance to the altar, that he should submit his throat to the knife, and expire without a struggle (23).

Even long after habitual cruelty had almost erased from the mind of man every make of affection for the inferior ranks of his fellow-creatures, 「74」 a certain respect was still paid to the principle of lie, and the crime of murdered innocence was in some degree atoned by the decent regard that was paid to the mode of their destruction.

________ Gentle friends,

Let’s kill him boldly, but not wrathfully:

Let’s carve him as a dish fit for the Gods;

Now hew him as a carcase fit for hounds;

And let our hearts, as subtle masters do,

Stir up their servants to an act of rage,

And after seem to chide them.

SHAKESPEARE.

「75」Such was the decency with which at fist the devoted victims were put to death.

But when man became perfectly civilized, those exterior symbols of sentiments, with which he was not but feebly if at all impressed, were also laid aside. Formerly sacrificed with some decorum to the pleas of necessity, the animals were now with unceremonious brutality destroyed, to gratify the unfeeling pride or wanton cruelty of men. Broad barefaced butchery 「76」 occupied every walk of life; every element was ransacked for victims; the most remote corners of the globe were ravished of their inhabitants, whether by the fastidious gluttony of man their flesh was held grateful to the palate, whether their blood could impurple the pall of his pride, or their spoils could add a tether to the wings of his vanity: and while nature, while agonizing nature is tortured by his ambition, while to supply the demands of his perverse appetite she bleeds at every 「77」 pore, this imperial animal exclaims; ye servile creatures, why do ye lament? why vainly try by cries akin to the voice of human woe my compassion to excite? Created solely for my use, submit without a murmur to the decrees of heaven, and to the mandates of me; of me the heaven-deputed despot of every creature that walks, or creeps, or swims, or flies in the air, on earth, or in the waters which encompass the earth. Thus the fate of the animal world has followed the progress of man from「78」 his sylvan state to that of civilization, till the gradual improvements of art, on this glorious pinnacle of independence, have at length placed him free from every tender link, free from every lovely prejudice of nature, and an enemy to life and happiness through all their various forms of existence.

But, famed for wisdom perhaps at a period more remote than what we claim as the æra of our creation, Hindostan never affected those pernicious arts, on which 「79」 we wish to establish a proud pretence to superior intelligence. Born at an earlier age of the world than other legislators can boast, Burmah, or whoever was the lawgiver of India (24), seems to have fixed by his precepts the lovely prejudices of nature, and to have prevented by his salutary institutions the baneful effects of subsequent refinement. Notwithstanding the frequent invasions of barbarians, European of Asiatic, and the consequent influx of various rites, the religion of Burmah,「80」congenial as it is to the gentle influence of the clime, and to the better feelings of the heart, bids fair to survive those foreign schemes of superstition, that tremble on the transient effervescence of that baleful enthusiasm to which they owe their birth. Disgusted with continual scenes of slaughter and desolation, pierced by the incessant shrieks of suffering innocence, and shocked by the shouts of persecuting brutality, the humane mind averts abhorrent from the view, and turning her「81」 eyes to Hindostan, swells with hearth-felt consolation on the happy spot, where mercy protects with her right hand the streams of life, and every animal is allowed to enjoy in peace the portion of bliss which nature prepared it to receive.

To where the far fam’d Hippemolgian strays,

Renown’d for justice, and for length of days,

Thrice happy race ! that, innocent of blood,

From milk innoxious seek their simple food;

Love sees delighted, and avoids the scene

Of guilty Troy.— POPE’s Homer’s Iliad.

May the benevolent system spread to every corner of the 「82」 globe; may we learn to recognize and to respect in other animals the feelings which vibrate in ourselves; may we be led to perceive that those cruel repasts are not more injurious to the creature whom we devour than they are hostile to our health, which delights in innocent simplicity, and destruction of our happiness, which is wounded by every act of violence, while it feeds as it were on the prospect of well being, and is raised to highest summit of enjoyment by the sympathetic touch of social satisfaction.