Edward Carpenter

The Art of Creation

Essays on the Self and Its Powers

「1904」Edward Carpenter, The Art of Creation: Essays on the Self and Its Powers「Google Books」(New York and London, 1904).

It is curious that we admit intelligence in Man, though we cannot prove it. I am hopeful that you perceive some intelligence in me. But you cannot absolutely prove that I feel and think; for all you know I may be merely a cleverly-made automation. You only infer that I feel and think from a comparison of my actions and movements with your own. And so, on the same grounds, we infer intelligence in dogs and monkeys, because their movements still resemble ours in some degree.「But we must remember that Descartes and other philosophers have contended that animals were merely machines or automata without feeling; and certainly one is almost obligated to think that some of our vivisection Professors adopt the same view.」When, however we come to creatures who movements do not much resemble ours ,like worms and oysters and trees, it is noticeable that we become very doubtful as to whether they feel or are conscious ,and even disinclined to admit they are. Yet it is obviously only a question of degree; and if we allow intelligence in our fellow men and women, and then in dogs, horses, and so forth, where and at what particular point are we to draw the line? In fact, it is obvious that the main reason why we do not allow intelligence in an oyster is because we do not understand and interpret its movements as well as we do those of a dog. But it is quite conceivable that to one of its own kind another oyster may appear the most lovely and intelligent being in creation. (The Art of Creation, 27-28)

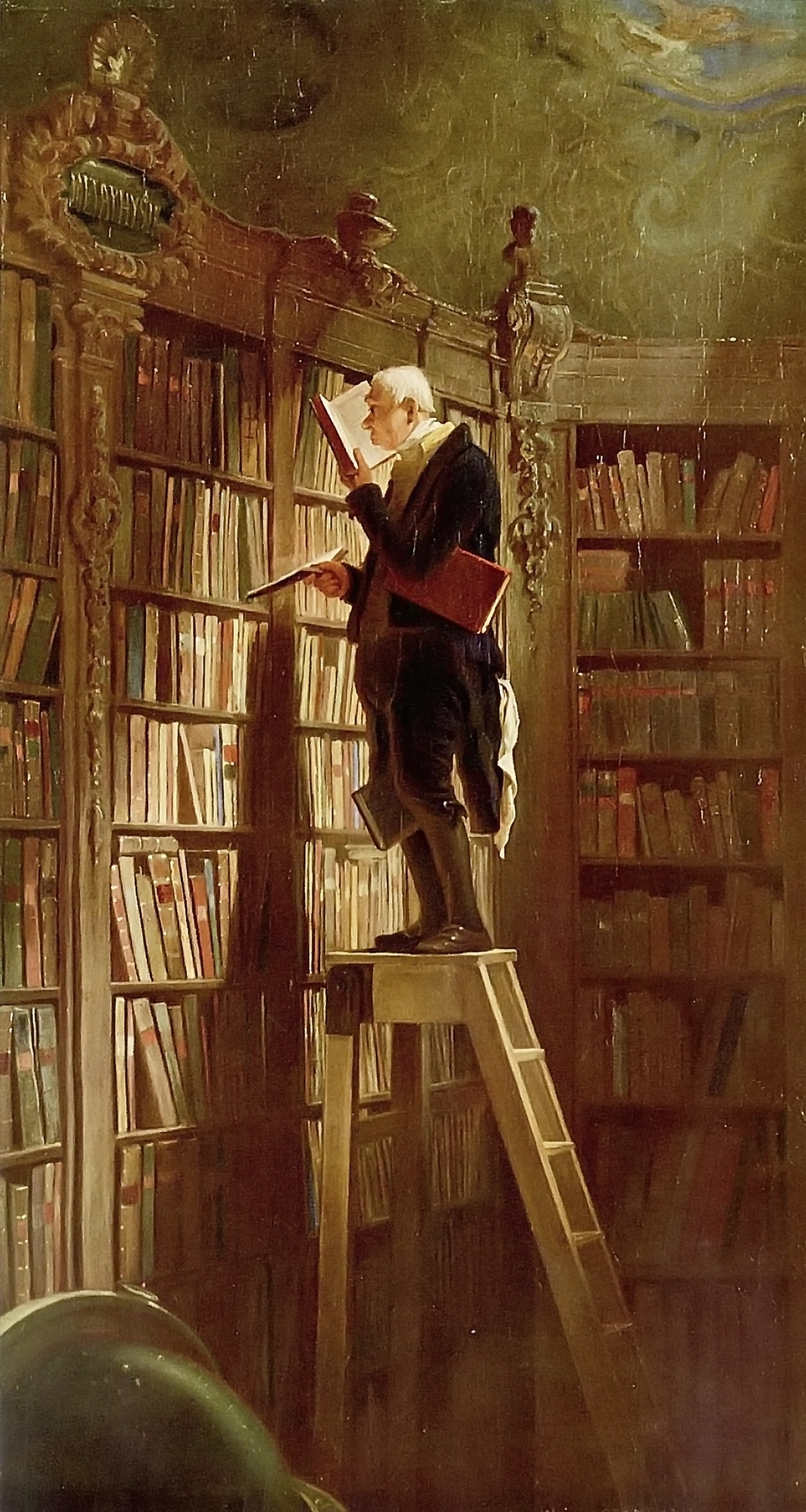

We conclude the intelligence of our friends because we should find it absurd and impossible to place ourselves on a lonely pinnacle and look upon those we love as automations. And in the same way, in proportion as we come to love and understand the animals and the trees and the face of Nature shall we find it impossible to deny intelligence to these…”A sense sublime,” as Wordsworth has it. (The Art of Creation, 31)

Such then is the first birth of self-consciousness. But as the evolution of the idea of self goes on, there comes at last a kind of fatal split between it and the objective side of things… Objects are soon looked upon as important only in so far as they minister to the (illusive) self; and there sets in the stage of Civilisation, when self-consciousness becomes almost a disease; when the desire of acquiring and grasping objects, or of enslaving men and animals, in order to minister to the self, becomes one of the main motives of life; and when, owing to this deep fundamental division in human nature and consciousness, men’s minds are tormented with the sense of sin, and their bodies with a myriad forms of disease. (Three Stages of Consciousness, 50)

Under Marcus Aurelius a wider sense of humanity was growing up. Hospitals, orphan schools, hospitals for animals even, began to be founded. (Three Stages of Consciousness, 153)

New ideals, new qualities, new feelings and envisagements of the outer world, are perpetually descending from within, both in man and the animals. (Transformation, 211)

Love and Sympathy: The self, hitherto deeming itself a separate atom, suddenly becomes aware of its inner unity with these other human beings, animal, plants even. It is as if a veil had been drawn aside. A deep understanding, knowledge, flows in. Love takes the places of ignorance and blindness; and to wound another is to wound oneself. It is the great deliverance from the prison-life of the separate self, and comes to the latter sometimes with the force and swiftness of a revelation. (Transformation, 218)

The sublime Consciousness of simple Being (with which we began these chapters) is there—is in the world and within all creatures—las the supreme Consciousness always. It can be seen quite plainly in the look in the eyes of the animals—and in primitive healthy folk and children—deep down, unsuspected by the creature itself; and yet there, unmistakable. It is seen by lovers in each other’s eyes—the One, absolute and changeless, yet infinitely individuate and intelligent— the Supreme life and being; of which all actual existence and Creation is the descent and partial utterance in the realms of emotion and thought. (Transformation, 222)

Not all to be one at once, certainly; but to be done—in time. I would not say “Be foolish or rash”; but surely it is itself the height of rashness not to run a risk now and then, hiding ourselves as we do all day behind innumerable mufflers and the torn-off skins of animas, and in our stuffy den, till we turn sickly pale all over like unwholesome crickets, and verily fear to venture out, lest she, Nature, the argus-eyes, see us and slay us in her wrath. (Health A Conquest, 244)