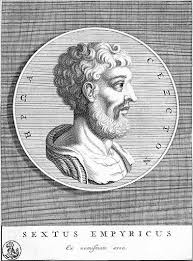

Sextus Empiricus

Pyrrhonic Sketches

Have the So-Called Irrational Animals Reason?

「2nd or 3rd c.」 Sextus Empiricus, “Have the So-called Irrational Animals Reason?” in the First of the Ten Troupes, Chapter 14 of Book 1 in Pyrrhonic Sketches, translated in Sextus Empircus and Greek Scepticism, by Mary Mills Patrick (Switzerland, 1897; Google Books: Online Library of Free eBooks).

We continue the comparison of the so-called irrational animals with man, although it is needless to do so, for in truth we do not refuse to hold up to ridicule the conceited and bragging Dogmatics, after having given the practical arguments. Now most of our number were accustomed to compare all the irrational animals together with man, but because the Dogmatics playing upon words say that the comparison is unequal, we carry our ridicule farther, although it is most superfluous to do so, and fix the discussion on one animal, as the dog, if it suits you, which seems to be the most contemptible animal; for we shall even then find that animals, about which we are speaking, are not inferior to us in respect to the trustworthiness of their perceptions. Now the Dogmatics grant that this animal is superior to us in sense perception, for he perceives better through smell than we, as by this sense he tracks wild animals that he cannot see, and he sees them quicker with his eyes than we do, and he perceives them more acutely by hearing. Let us also consider reasoning, which is of two kinds, reasoning in thought and in speech. Let us look first to that of thought. This kind of reasoning, judging from the teachings of those Dogmatics who are now our greatest opponents, those of the Stoa, seems to fluctuate between the following things: the choice of the familiar, and avoidance of the alien; the knowledge of the arts that lead to this choice; and the comprehension of those virtues that belong to the individual nature, as regards the feelings. The dog then, upon whom it was decided to fix the argument as an example, makes a choice of things suitable to him, and avoids those that are harmful, for he hunts for food, but draws back when the whip is lifted up; he possesses also an art by which he procures the things that are suitable for him, the art of hunting. He is not also without virtue; since the true nature of justice is to give to every one according to his merit, as the dog wags his tail to those who belong to the family, and to those who behave well to him, guards them, and keeps off strangers and evil doers, he is surely not without justice. Now if he has this virtue, since the virtues follow each other in turn, he has the other virtues also, which the wise men say, most men do not possess. We see the dog also brave in warding off attacks, and sagacious, as Homer testified when he represented Odysseus as unrecognised by all in his house, and recognised only by Argos, because the dog was not deceived by the physical change in the man, and had not lost the φαντασία καταληπτική which he proved that he had kept better than the men had. But according to Chrysippus even, who most attacked the irrational animals, the dog takes a part in the dialectic about which so much is said. At any rate, the man above referred to said that the dog follows the fifth of the several non-apodictic syllogisms, for when he comes to a meeting of three roads, after seeking the scent in the two roads, through which his prey has not passed, he presses forward quickly in the third without scenting it. For the dog reasons in this way, potentially said the man of olden time; the animal passed through this, or this, or this; it was neither through this nor this, therefore it was through this. The dog also understands his own sufferings and mitigates them. As soon as a sharp stick is thrust into him, he sets out to remove it, by rubbing his foot on the ground, as also with his teeth; and if ever he has a wound anywhere, for the reason that uncleansed wounds are difficult to cure, and those that are cleansed are easily cured, he gently wipes off the collected matter; and he observes the Hippocratic advice exceedingly well, for since quiet is a relief for the foot, if he has ever a wound in the foot, he lifts it up, and keeps it undisturbed as much as possible. When he is troubled by disturbing humours, he eats grass, with which he vomits up that which was unfitting, and recovers. Since therefore it has been shown that the animal that we fixed the argument upon for the sake of an example, chooses that which is suitable for him, and avoids what is harmful, and that he has an art by which he provides what is suitable, and that he comprehends his own sufferings and mitigates them, and that he is not without virtue, things in which perfection of reasoning in thought consists, so according to this it would seem that the dog has reached perfection. It is for this reason, it appears to me, that some philosophers have honoured themselves with the name of this animal. In regard to reasoning in speech, it is not necessary at present to bring the matter in question. For some of the Dogmatics, even, have put this aside, as opposing the acquisition of virtue, for which reason they practiced silence when studying. Besides, let it be supposed that a man is dumb, no one would say that he is consequently irrational. However, aside from this, we see after all, that animals, about which we are speaking, do produce human sounds, as the jay and some others. Aside from this also, even if we do not understand the sounds of the so-called irrational animals, it is not at all unlikely that they converse, and that we do not understand their conversation. For when we hear the language of foreigners, we do not understand but it all seems like one sound to us. Furthermore, we hear dogs giving out one kind of sound when they are resisting someone, and another sound when they howl, and another when they are beaten, and a different kind when they wag their tails, and generally speaking, if one examines into this, he will find a great difference in the sounds of this and other animals under different circumstances; so that in all likelihood, it may be said that the so-called irrational animals partake also in spoken language. If then, they are not inferior to men in the accuracy of their perceptions, nor in reasoning in thought, nor in reasoning by speech, as it is superfluous to say, then they are not more untrustworthy than we are, it seems to me, in regard to their ideas. Perhaps it would be possible to prove this, should we direct the argument to each of the irrational animals in turn. As for example, who would not say that the birds are distinguished for shrewdness, and make use of articulate speech? for they not only know the present but the future, and this they augur to those that are able to understand it, audibly as well as in other ways. I have made this comparison superfluously, as I pointed out above, as I think I had sufficiently shown before, that we cannot consider our own ideas superior to those of the irrational animals. (118-22)