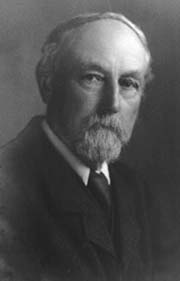

Henry Salt

Animals’ Rights

「1892」 Henry Salt, Animals’ Rights Considered in Relation to Social Progress, with a Bibliographical Appendix「Google eBook」(London & New York, 1892; 1894; Online at Animal Rights History, 2003).

The object of the following essay is to set the principle of animals’ rights on a consistent and intelligible footing, to show that this principle underlies the various efforts of humanitarian reformers, and to make a clearance of the comfortable fallacies which the apologists of the present system have industriously accumulated.

Enlightened thinkers provide support for Salt’s assertion that “animals as well as men…are possessed of a distinctive individuality, and, therefore are in justice entitled to live their lives with a due measure of that ‘restricted freedom'”

(6), “the right to live a natural life—a life, that is, which permits of the individual development—subject to the limitations imposed by the permanent needs and interests of the community”

(22).

Quoting 19th century humanitarians, he underscores the fallacious reasoning in religious arguments: that animals are “without souls”

(8), and those based on Descartes’ theory that animals are mere “animated machines”

and “have no moral purpose” (10). He admonishes the usage of such terms as “brute–beast”

and “live–stock”

which perpetuate the absurdity of a “lack of individuality”

in animal creation, “ignoring the fact that man is an animal no less than they”

(14-15).

Applying this “general principle of animals’ rights”

(23) to issues relating to domestic (24) and wild animals (36), the use of animals for food (43), sport (53), fashion (63) and science (72), he proves the preposterousness of arguments supporting such cruelties. Addressing criticisms and demands of opponents, Salt offers encouragement to humanitarian workers and reformers (18). In conclusion, Salt argues that “to advocate the rights of animals is far more than to plead for compassion or justice towards the victims of ill-usage; but for the sake of mankind itself, our true civilisation, our race-progress, our humanity”

(88).

______

ANIMALS’ RIGHTS

“I saw deep in the eyes of the animals the human soul look out upon me.

“I saw where it was born deep down under feathers and fur, or condemned for awhile to roam four–footed among the brambles. I caught the clinging mute and swore that I would be faithful.

“Thee my brother and sister I see and mistake not. Do not be afraid. Dwelling thus for a while, fulfilling thy appointed time—thou too shaft come to thyself at last.

“Thy half–warm horns and long tongue lapping round my wrist, do not conceal thy humanity any more than the learned talk of the pedant conceals his—for all thou art dumb, we have words and plenty between us.

“Come nigh, little bird, with your half–stretched quivering wings—within you I behold choirs of angels, and the Lord himself in vista.”

Towards Democracy.

ANIMALS’ RIGHTS

CONSIDERED IN RELATION TO SOCIAL PROGRESS

WITH A BIBLIOGRAPHICAL APPENDIX

BY

HENRY S. SALT

AUTHOR OF “THE LIFE OF HENRY DAVID THOREAU”

__________

ALSO AN ESSAY

ON VIVISECTION IN AMERICA

BY

ALBERT LEFFINGWELL, M.D.

AUTHOR OF “ILLEGITIMACY: A STUDY IN DEMOGRAPHY,”

“RAMBLES IN JAPAN,” ETC.

NEW YORK

MACILLAN & CO.

AND LONDON

1894

COPYRIGHT, 1894 BY

MAGMILLAN & CO.

[Transcriber’s Note: The above was stamped with XX over the above copyright and included the following notation:」

Extracts from this book may be reprinted to any extent desired.

TROW DIRECTORY

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY

NEW YORK

Prefatory Note

The object of the following essay is to set the principle of animals’ rights on a consistent and intelligible footing, to show that this principle underlies the various efforts of humanitarian reformers, and to make a clearance of the comfortable fallacies which the apologists of the present system have industriously accumulated. While not hesitating to speak strongly when occasion demanded, I have tried to avoid the tone of irrelevant recrimination so common in these controversies, and thus to give more unmistakable emphasis to the vital points at issue. We have to decide, not whether the practice of fox-hunting, for example, is more, or less, cruel than vivisection, but whether all practices which inflict unnecessary pain on sentient beings are not incompatible with the higher instincts of humanity.

I am aware that many of my contentions will appear very ridiculous to those who view the subject from a contrary standpoint, and regard the lower animals as created solely for the pleasure and advantage of man ; on the other hand, I have myself derived an unfailing fund of amusement from a rather extensive study of our adversaries’ reasoning. It is a conflict of opinion, wherein time alone can adjudicate; but already there 「vi」 are not a few signs that the laugh will rest ultimately with the humanitarians.

My thanks are due to several friends who have helped me in the preparation of this book; I may mention Mr. Ernest Bell, Mr. Kenneth Romanes, and Mr. W. E. A. Axon. My many obligations to previous writers are acknowledged in the foot–notes and appendices.

H. S. S.

September, 1892

CONTENTS

ANIMALS’ RIGHTS

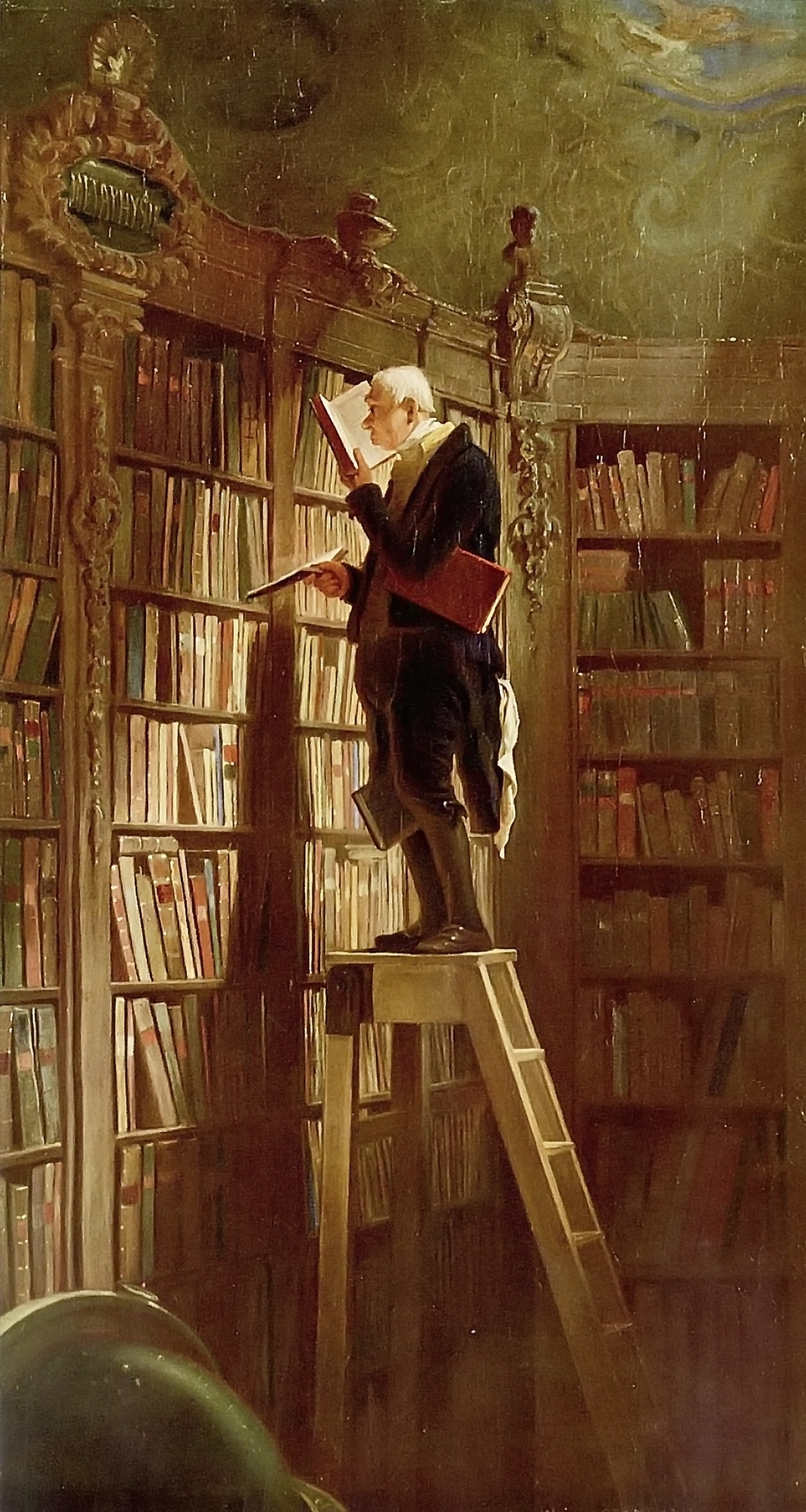

CHAPTER I. THE PRINCIPLE OF ANIMALS’ RIGHTS.

The general doctrine of rights ; Herbert Spencer’s definition. Early advocates of animals’ rights; “Martin’s Act,” 1822. Need of an intelligible principle. Two main causes of the denial of animals’ rights: (1) The “religious” notion that animals have no souls, (2) the Cartesian theory that animals have no consciousness. The individuality of animals. Opinions of Schopenhauer, Darwin, etc. The question of nomenclature ; objectionable use of such terms as “brute beast,” etc. The progressiveness of humanitarian feeling ; analogous instance of negro slavery. Difficulties and objections; arguments drawn from “the struggle of life.” Animals’ rights not antagonistic to human rights. Summary of the principle

. . . pp. 1-23

CHAPTER II. THE CASE OF DOMESTIC ANIMALS.

Special claims of the domestic animals ; services performed by them ; human obligations in return. Opinions of Humphry Primatt and John Lawrence. Common disregard of rights in the case of horses, cattle, sheep, etc. Castration of animals. Treatment of dogs and cats. Condition of the household “pet” compared with that of the “beast of burden”

. . . pp. 24-35

CHAPTER III. THE CASE OF WILD ANIMALS

Wild animals have rights, though not yet recognized in law. The influence of property. Man not justified in injuring any harmless animal. The condition of animals in menageries ; the fallacy that “they gain by it.” Caged birds. A right relationship must be based on sympathy, not power

. . . pp. 36-42

CHAPTER IV. THE SLAUGHTER OF ANIMALS FOR FOOD

Important bearing of the food question on the consideration of animals’ rights. The assumption that flesh–food is necessary ; contradictory statements of flesh–eaters. Experience proves that man is not compelled to kill animals for food. Cruelties inseparable from slaughtering ; feeling of repugnance thereby aroused. The logic of these facts. Ingenious attempts at evasion : “Animals would otherwise not exist ;” “scriptural permission.” The coming success of food–reform

. . . pp. 43–52

CHAPTER V. SPORT, OR AMATEUR BUTCHERY

Sport the most wanton of all violations of animals’ rights. Childish fallacies of sportsmen. Tame stag–hunting ; rabbitcoursing ; cruel treatment of “vermin ;” steel traps. The testimony of an expert on cover–shooting

. . . pp. 53–62

CHAPTER VI. MURDEROUS MILLINERY

The fur and feather traffic. In what sense it is “necessary ;” the use of leather. Fashionable demand for furs causes whole provinces to be ransacked. The wearing of feathers in bonnets ; heartless massacre of birds. Due to ignorance and thoughtlessness

. . . pp. 63–71

CHAPTER VII. EXPERIMENTAL TORTURE

The analytical methods of scientists and naturalists. Vivisection the logical outcome of this mood. The horrors of vivisection. Its alleged utility. Moral considerations involved ; nothing that is inhuman can be in accord with true science. Experiments on animals as compared with experiments on men. The plea that vivisection is “no worse” than other cruelties. The exact significance of vivisection in the question of animals’ rights

. . . pp. 72–82

The lesson of the foregoing instances of cruelty and injustice ; the only solution of the problem is to recognize animals’ rights. No “sentimentality,” where difficulties are fairly faced. The future path of humanitarianism. Human interests involved in animals’ rights ; extension of the idea of “humanity” both in western thought and oriental tradition. The movement essentially a democratic one; the emancipation of man will bring with it the emancipation of animals. Practical steps toward securing the rights of animals : (1) Education. Useless to preach humanity to children only; need of an intellectual and literary crusade. The laugh to be turned against the real sentimentalists, our opponents. (2) Legislation. Laisser–faire objections refuted. Cases where immediate action is desirable. Conclusion

. . . pp. 83–104

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE RIGHTS OF ANIMALS

. . . pp. 105–132

CONTENTS. VIVISECTION IN AMERICA.

CHAPTER I. VIVISECTION IN MEDICAL SCHOOLS

Conflicting opinions. What are “abuses” of vivisection? Experiments of Brachet, Castex, Von Lesser, Chauveau, Mantagazza, and others. The absence of restraints always invites excesses. No safeguards against the abuse of experimentation exist in any part of America. What has been done in the United States. Opinion of Dr. Bigelow, of Harvard University. The British Medical Journal on certain American “original investigations.” Prevention of abuses, by State restriction and supervision.

. . . pp. 133–146

CHAPTER II. VIVISECTION IN AMERICAN COLLEGES

The new scientific ideal. Biology in the American university. Opportunities for its study at Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Cornell, University of Michigan, and others. The use of torture as for illustration of science–teaching. The atrocious experiment of Stricker, of Vienna. What prevents its repetition in American colleges? Have any restrictions been made by the leading colleges, regulating or forbidding the use of prolonged torture of animals, in the study of physiology? Correspondence with college presidents. No impediments at present hinder the infliction of any degree of torment desired in any of the principal American colleges. Suggested reforms. The responsibility for low ideals. The hope for the future.

. . . pp. 147–168

APPENDIX A. THE LINES OF PERSONAL INVESTIGATION ADVISED, REGARDING VIVISECTION

. . . pp. 147–168

APPENDIX B. THE AMERICAN HUMANE ASSOCIATION ON RESTRICTION OF VIVISECTION

. . . pp. 145–176