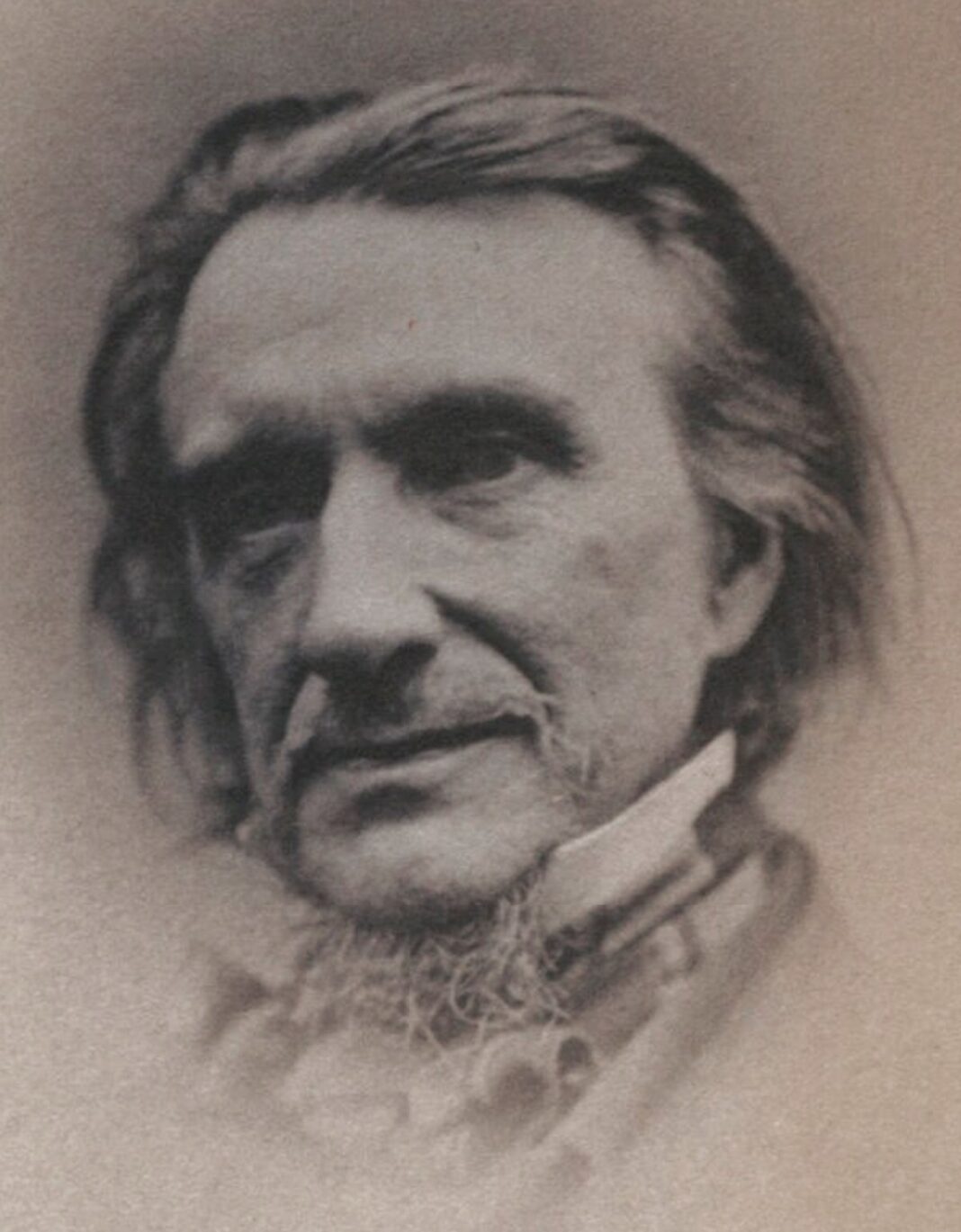

Francis William Newman

Theism, Doctrinal and Practical; Didactic Religious Utterances

Rights of Animals

「1857」 Francis William Newman, “Rights of Animals,” in Theism, Doctrinal and Practical; or, Didactic Religious Utterances「Google Books」(London, 1857) 179-182.

RIGHTS OF ANIMALS.

How pleasant is it to see beautiful creatures, otherwise wild,

Become tame and trustful to the hand of man,

Or at least not terrified by his near approaches !

As when the gentle fallow deer loves to be fondled,

And the hare and the pheasant are not scared,

Or the stork calmly builds its nest on the housetop.

The life of such animals may be taken for man’s need,

Yet it is not indifferent in what way it be taken;

Whether so as only to cut short the days of the individual,

Or so as also to distress and terrify the living,

Chasing them from pleasant haunts into distant refuge less hospitable,

And filling them with terror of man their enemy.

The more intelligent the animal, the worse the infliction;

For he remembers both the causes of danger and its neighbourhoods,

And by his sagacity shuns new encounter with the more powerful.

Thus the beaver is driven from his rivers and favourite pools.

Thus the gentle seal, massacred in heaps by sailors,

Forsakes milder seas and its well-known creeks,

Plunging into drearier mist and further ice,

Which punish not undeservedly the too relentless persecutor,

Who thought but of momentary gain by promiscuous slaughter,

And, slighting all rights of animals, was unwise for his own future.

That all living things have some rights, no one will deny;

For wanton cruelty is universally condemned:

Yet the limits of their rights have been scarcely discussed,

Nor the diverse rights of diverse animals

Under circumstances diverse, such as tame and wild.

The tame creature which receives and gives affection

Is with most humane persons a sacred life;

Nor will many approve to slaughter a pet lamb

Or a much fondled gazelle, for daintiness and avarice;

Though for any real necessity the same cannot be disapproved.

Not but that it is well pressed by advocates of Vegetarianism,

That for taking animal life a grave justification is needed.

If health, strength and comfort, with equal longevity,

Can be sustained on other food, especially with less human labour,

No reason for depriving animals of sweet life remains,

Much less for wounding and killing with cruelty

Such creatures as have exquisite sensitiveness equal to ours.

No excess of birds need be feared, if we let alone their natural foes.

Nor reply thou, that thus also they will be cruelly killed.

The hawk and the weasel kill with certainty and with ease.

The cattle that multiply under man’s care and protection,

Who in some sense may be said to have bestowed life upon them;

Such cattle, if not admitted into personal attachment,

Nor endowed with sagacity to foresee or to remember deaths,

Are slain for man’s use without moral mischief,

On condition that the slaughter be sudden and complete.

Not but that even here, caution may justly be entered,

Against so inflicting death as to wound those who live.

To kill a calf while the mother will grieve for it,

Does not merely shorten a life, but tortures maternal feeling,

Which exists in the cow less intelligently than in the woman,

Yet not less truly or less unfailingly:

And even if man’s nobler life be well fed by animal life,

Yet daintiness of appetite, though in a man, is less noble

Than maternal affection, though it be but in a cow:

And a better morality than that hitherto called Christian

Will hereafter enact a sharper limit of our rights over the animal.

In fact over wild creatures, which man has never protected

Nor fed, nor in any way reared, we have no direct claim;

For neither strength over weakness nor cunning over simplicity

Gives any validity of right, except for protection and government.

But the creatures which exist without mutual affection,

Having neither family life nor maternal sentiment, Living for themselves alone, grieving for none,

Have not even the rudiments of morality or of moral rights:

And where life is wholly unmoral, we are free to take it.

Thus man captures and devours the fish of seas and rivers,

As innocently as the same fish devour one another,

Violating no tender affection nor engendering moral evil.

Less clear by far is the case with animals intelligent and affectionate,

Which love their own comrades and resent their wrongs;

As the troops of walrus and of seal assemble for vengeance,

If but one of their own band has been harmfully assailed;

And mourn over the slaughtered, and piteously remember the place:—

Creatures sensible and kind, not less sagacious than dogs,

Curious of man’s ways and of the sweet sounds of music,

So that, but for their marine life, sea-dogs would be our faithful friends.

Surely, to harass these creatures is not without its evil

In the eye of the great God who inspires their mutual love.

Nor can other destructive commercial hunting be approved.

As, where the majestic bison ranges the prairie,

Cut off by wild forest and swamp from inhabited lands;

The hunters, incited by trade, kill the noble game without measure,

Strewing the ground with (it may be) four hundred huge carcases,

And carry away but four hundred wretched tongues!

Many such are the enormities where Law cannot reach.

While human tribes shall live on the grounds of the bear and wolf,

Driven thither by tyrannies or detained by ignorance

And by bodily habits half assimilated to the brutal,

So long the wild seal must perish for the wild man.

But the times of man’s misgovernment are not to be eternal,

Nor can eternal morality be framed out of transitory facts;

And those who have learnt well that the Moral is higher than the Material,

Will not despise tender affection though in the bosom of ape or bear.

On the Galipagos Islands, where men have not dwelt permanently,

In respect of birds and beasts, is a modern garden of Eden,

Where birds settle on the buckets while men are carrying them.

Oh how great the delight to live among birds thus tame!

What man is so void of sentiment as rather to wish to eat them?

The Turk, the Arab, the Indian,—men individually rude—

Are often taught by religion to revere God’s gift of life,

And to abhor destroying life save for security or need.

To enjoy acts of slaughter, and the sport of killing,

Belonged (once upon a time) to none but wild barbarians,

In whom hunting had engendered a love of mere destruction.

It is reserved for modern times, and pre-eminently for Christians,

That humane and refined men should sport with deeds of blood,

Killing and wounding the timid, the gentle, the beautiful,

Not for food nor even for daintiness, but for the pride of skill.

What tender and thoughtful heart will call such pastime pleasure,

And think without compunction over the lingerings of the wounded?