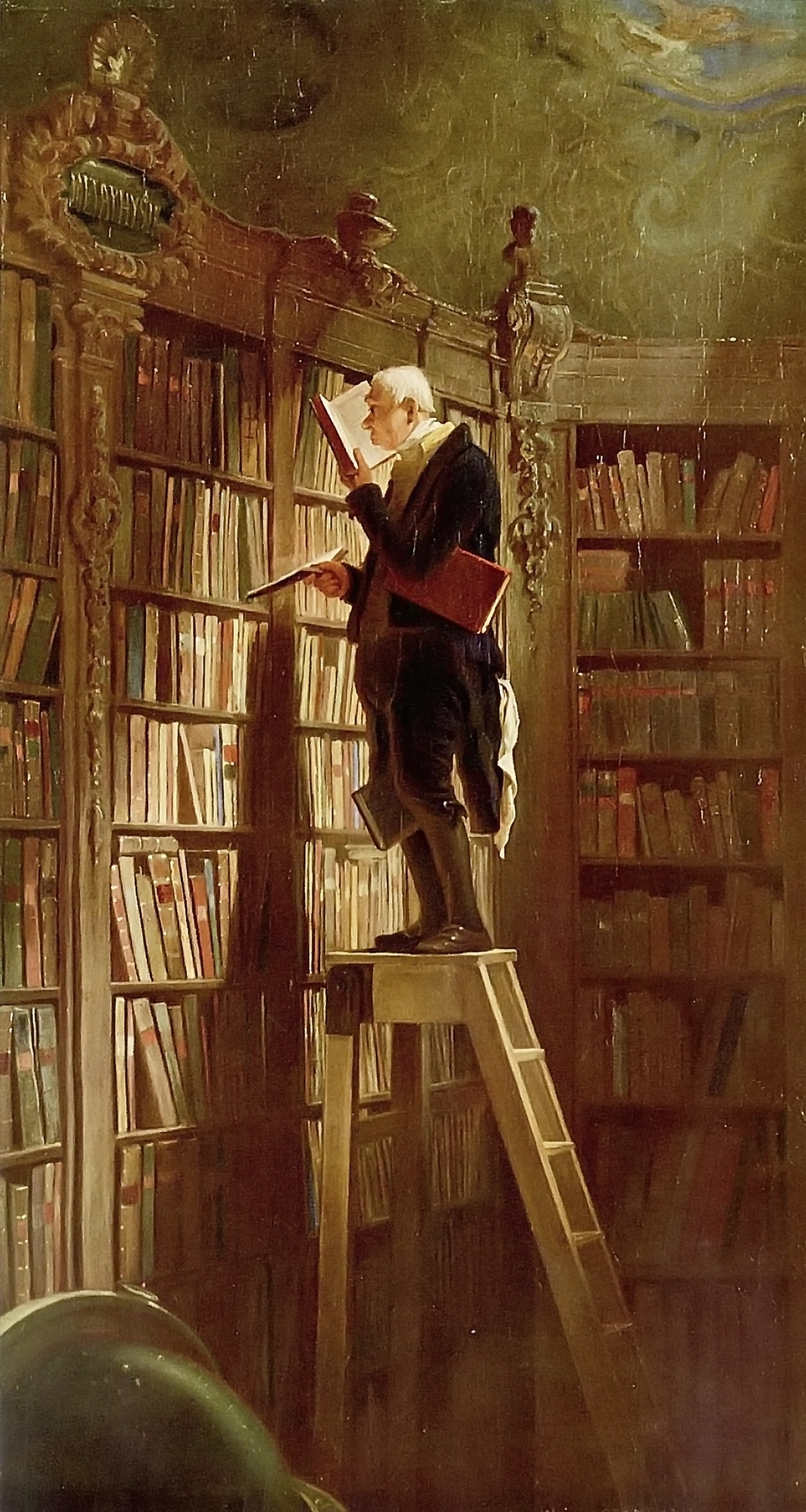

Mrs. Anna Jameson

A Commonplace Book of Thoughts, Memories and Fancies,

Original and Selected

「1854」Mrs. Anna Jameson, “Notes from Books,” in A Commonplace Book of Thoughts, Memories, and Fancies, Original and Selected 「Google Books」(London, 1854) 207-214.

There is nothing, as I have sometimes thought, in which men so blindly sin as in their appreciation and treatment of the whole lower order of creatures. Its is affirmed that love and mercy towards animals are not inculcated by any direct precept of Christianity, but surely they are included in its spirit.

Bacon, in his “Advancement of Learning,” does not think it beneath his philosophy to pint out as a part of human morals, and a condition of human improvement, justice and mercy to the lower animals— “the extension of a noble and excellent principle of compassion to the creatures subject to man.”

It should seem as if the primitive Christians, by laying so much stress upon a future life in contradistinction to this life, and placing the lower creatures out of the pale of hope, placed them at the same time out of the pale of sympathy, and thus laid the foundation of this utter disregard of animals in the light of our fellow creatures. Their definition of virtue was the same as Paley‘s —that it was good performed for the sake of ensuing everlasting happiness—which of course excluded all the so-called brute creatures. Kind, loving, submissive, conscientious, much-enduring, we know them to be; but because we deprive them of all stake in the future, because they have no selfish calculated aim, these are not virtues; yet if we say “a vicious horse,” why not say a virtuous horse.

The following passage, bearing curiously enough on the most abstruse part of the question, I found in Hallam’s Literature of the Middle Ages: — “Few,” he says, ” at present, who believe in the immateriality of the human soul, would deny the same to an elephant; but it must be owned that the discoveries of zoology have pushed this to consequences which some might not readily adopt. The spiritual being of a sponge revolts a little our prejudices; yet there is no resting-place, and we must admit this, or be content to sink ourselves into a mass of medullary fibre. Brutes have been as slowly emancipated in philosophy as some classes of mankind have been in civil polity; their souls, we see, were almost universally disputed to them at the end of the seventeenth century, even by those who did not absolutely bring them down to machinery. Even within the recollection of many, it was common to deny them any kind of reasoning faculty, and to solve their most sagacious actions by the vague word instinct. We have come of late years to think better of our humble companions; and, as usual in similar cases, the preponderant bias seems rather too much of a levelling character.”

When natural philosophers speak of ” the higher reason and more limited instincts of man,” as compared with animals, do they mean savage man or cultivated man ? In the savage man the instincts have a power, a range, a certitude, like those of animals. As the mental faculties become expanded and refined the instincts become subordinate. In tame animals are the instincts as strong as in wild animals ? Can we not, by a process of training, substitute an entirely different set of motives and habits?

Why, in managing animals, do men in general make brutes of themselves to address hwat is most brute in the lower creature, as if it had nto been demonstrated that in using our higher faculties, or reason and benevolence, we develop sympathetically higher powers in them, and in subdoing them thourgh what is best in us, raise them and bring them nearer to ourselves?

In general the more we can gather the facts, the nearer we are to the elucidation of theoretic truth. But with regard to animals, the multiplication of facts only increases our difficulties and puts us to confusion.

“Can we otherwise explain animal instinct that by supposing that the Deity himself is virtually the active and present moving principle within them? If we deny them soul, we must admit that hey have some spirit within them? If we deny them soul, we must admit that they have some spirit direct from God, what we call unerring instinct, which holds the place of it.” This is the opinion which Newton adopts. Then are we to infer that the reason of man removes him further from God than the animals, since we cannot offend God in our instincts, only in our reason? And that the superiority of the human animal lies in the power of sinning? Tterrible power? terrible privilege! Out of which we deduce the law of progress and the necessity for a future life.

The following passabe bearing on the subject is from Bentham:—

“The day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been withholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. It may come one day to be recognised that the number of legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum, are reasons insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the caprice of a tormentor. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? is it the faculty of reason, or, perhaps, the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog is beyond comparison a more rational as well as a more conversable animal than an infant of a day, a week, or even a month old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail ? The question is not, ‘ can they reason ?’ nor ‘ can they speak ?’ but ‘ can they suffer ? “‘

I do not remember ever to have heard the kind and just treatment of animals enforced upon Christian principles or made the subject of a sermon.

Once, when I was at Vienna, there was a dread of hydrophobia, and orders were given to massacre all the clogs which were found unclaimed or uncollared in the city or suburbs. Men were employed for this purpose, and they generally carried a short heavy stick, which they flung at the poor proscribed animal with such certain aim as either to kill or maim it mortally at one blow. It happened one day that, close to the edge of the river, near the Ferdinand’s Briicke, one of these men flung his stick at a wretched dog, but with such bad aim that it fell into the river. The poor animal, following his instinct or his teaching, immediately plunged in, redeemed the stick, and laid it down at the feet of its owner, who, snatching it up, dashed out the creature’s brains.

I wonder what the Athenians would have done to such a man? they who banished the judge of the Areopagus because he flung away the bird which had sought shelter in his bosom ?