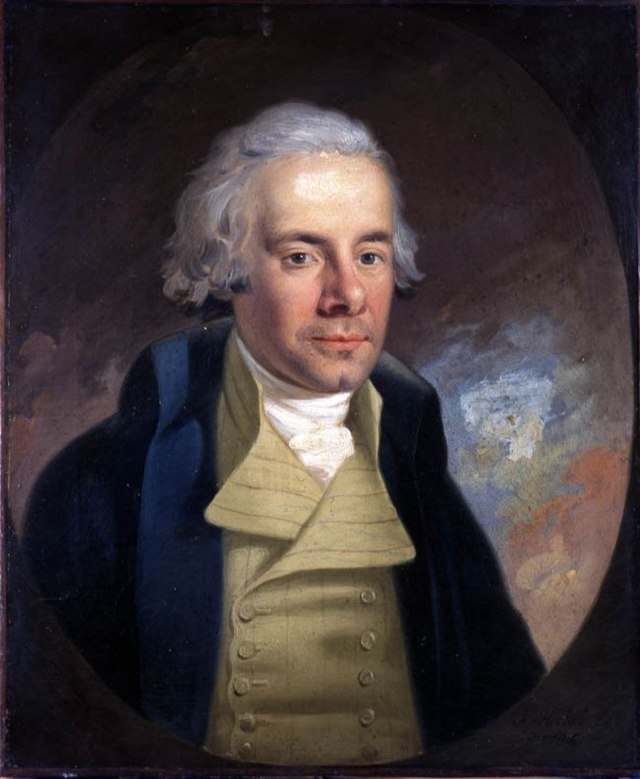

William Wilberforce

Bull-Baiting Bill 1800 and 1802

「1800-Apr-25」”William Wilberforce to Mrs. Hannah More,” extracted in vol. 2 of The Life of William Wilberforce by his sons, Robert and Samuel Wilberforce「Google Books」(London, 1838).

He was much “hurt,” he tells Mrs. Hannah More this session, at the defeat of another measure bearing upon the interest of the people. “Sir William Pulteney, who brought forward the bill to suppress bull-baiting at the instance of some people of the country, (I declined because I am a common hack in such services, but I promised to move it if nobody else would,) argued it like a parish officer, and never once mentioned the cruelty. No summonses for attendance were sent about as is usual. In consequence not one, Thornton, nor many others, were present, any more than myself. I had received from some country magistrates and account of the barbarities practised in this generous pastime of Windham’s, which would e surpassed only by the tortures of an Indian warrior. A Surrey magistrate told a friend of mine yesterday, that some people met for a boxing match, and the magistrates proceeding to separate them, they threw their hats into the air, and declaring Mr. Windham had defended boxing in parliament, called out, “Windham and Liberty.” A strange and novel association, by the way! Canning, to do him justice, was ashamed of himself, and told me when I showed him the account of the cruelties, (which Windham read coldly,) that he had no idea of the real nature of the practice he had been defending. Alas! alas! we bear about us multiplied plague spots, sure indications of a falling state.

「1802-May-24」 “Debate in the Commons on the Bill to Prevent Bull-Baiting,” Parliamentary History 36 (1801-Oct-29 to 1803-Aug-03): 829-854.

Mr. Wilberforce thought that the subject had been treated with too much levity. If the good effects which had been attributed to it were really produced by bull-baiting, why not move to have it rendered more general? But the truth was, every argument employed to defend the practice had been merely palliative. Mere opinions had been stated to prove that it was nowise hurtful to morality; but for his own part, he thought it fostered every bad and barbarous principle of our nature; and he was sorry that any one so respectable as his right hon. friend had been found to defend it. He was certain if that right hon. gentleman, or any other member, had inquired into the subject minutely, he would no longer defend a practice which degraded human nature to a level with the brutes. The evidence against the practice was derived from respectable magistrates. From such evidence he had derived a variety of facts, which were too horrid to detail to the House. A bull, that honest, harmless, useful animal, was forcibly tied to a stake, and a number of bull-dogs set upon him. If he was not sufficiently roused by the pain of their attacks, the most barbarous expedients were hit upon to awake in him that fury which was necessary to the amusement of the inhuman spectators. One instance of the latter kind he would state; a bull had been bought for the sole purpose of being baited; but upon being fixed to the stake, he was found of so mild a nature, that all the attacks of the dogs were insufficient to excite him to the requisite degree of fury; upon which those who bought him refused to pay the price to the original owner, unless he could be made to serve their purpose: the owner, after numberless expedients, at last sawed off his horns, and poured into them a poignant sort of liquid, that quickly excited the animal to the wished-for degree of fury. When bulls were bought merely for the purpose of being baited, the people who bought them wished to have as much diversion (if diversion such cruelty could be called) as possible for their money. The consequence was, that every art, even fire, bad been employed to rouse the exhausted animal to fresh exertions, and there were instances where he had expired in protracted agonies amidst the flames. It had been said, that it would be wrong to deprive the lower orders of their amusements, of the only cordial drop of life which supported them under their complicated burthens. Wretched, indeed, must be the condition of the common people of England, if their whole happiness consisted in the practice of such barbarity! Such a supposition was a satire, not only on the name of Englishmen, but on the Creator who formed reasonable creatures with such barbarous propensities. Of all the arguments ever invented by Jacobinism to prove the wretched state of the lower orders, this surely was the strongest, if the only enjoyment of the common people of England was derived from the practice of bull-baiting. It had bean said, that this practice contributed to keep alive the martial ardour of the nation. But had it not been proved, by experience, that the greatest, the most renowned characters, had always been the most humane? When we considered that the victim of this human amusement was not left to the free exertion of his natural powers, but bound to a stake, and baited with animals instinctively his foes, and urged by acclamation to attack him, must we not conclude that the practice was inconsistent with every manly principle, cruel in its designs, and cowardly in its execution? No man was more unwilling than he was to encroach upon the amusements of the lower orders; on the contrary, he wished to rescue them from the ignominious reproach cast upon them, that they were so ignorant and so debased as to be fit only to enjoy the cowardly amusement of tormenting an harmless and fettered animal to death.—But it had been stated, that the present bill ought not to be passed, without also preventing shooting, hunting, and every other attack on inferior animals. Suppose these diversions to be equally inhuman, would not the admission of this argument infer, that no vice was to be abolished because all of the same species could not at once be done away? But it was by no means proper to place the diversions of shooting and horse-racing on a footing with bull-baiting. Shooting afforded exercise to the body, and the birds who fell by it were subjected to no pain beyond immediate deprivation of life. In horse-racing, two generous animals, with scarcely any compulsion, exerted their speed against each other, and returned from the course with small abatement of spirits or vigour. But bull-baiting not only excited the natural passions of the animal for the amusement of the spectators, but also subjected it to the most inhuman cruelties, till it sunk under the pressure of its complicated miseries. It was easy to dress up a metaphysical picture in one’s closet, till the author was led to admire the image of his own creation. But if instead of such refinements we attended to the voice of common sense, we should be convinced that no happiness could result from a practice so cruel, base, and unjust—that no pleasure could be derived from wantonly torturing the brutes which were given us, not for such barbarous purposes, but for our use and pleasure. Without such an amusement, the common people of England had surely a sufficient number of innocent amusements, in their festivals, their gambols, their athletic exercises. His right hon. friend, while picturing the happiness derived from bull-baiting, had forgot that it was confined to an individual, while his wretched family excluded from any participation of the spectacle, were condemned to feel the want of that money which he squandered away on such occasions. He had never heard a speech tending so strongly to make the people dissatisfied with their condition. It was not his wish to deprive them of their manly recreations, but he could not give this character to a diversion founded on cowardice and cruelty. Great writers had placed the summit of human happiness, not in picnics, but in the cottage of the peasant, surrounded with his smiling family. This was the happiness, and this the recreation, varied and combined with manly exercises abroad, which belonged naturally to the people of England; and he would not suffer them to be degraded by supposing, that like bull-dogs, they had an instinctive desire for this sport. One thing more he should take notice of, namely, the charge which the right hon. gentleman had made on him of jumping over the horse-racing. He was not himself a frequenter of horseraces; and though they were very frequent in the county which he had the honour to represent, it was not thought an indispensable duty in the representative of that county to frequent races. He repeated, however, that he did not think it so cruel to see two generous animals exert their powers against each other; and if there was any cruelty in horse-races, it was in the matches against time, which would have been a better theme for the right hon. gentleman’s censure, unless he had that in reserve as a public amusement after bull-baiting should be abolished. On a comparison of the different sports, it would be found that none of them partook of cruelty so largely as bull-baiting. No man could be partial to it, except from an imaginary view; a real knowledge would silence all its advocates.

「1802-May」”House of Commons, May 24, Second Reading of the Bill to Prevent Bull-Baiting,” Edinburgh Magazine 19 (1802-Oct): 461-4.

Mr. Wilberforce said he had heard a great deal, as if the lower orders of the people were in a state totally devoid of all other alleviation or amusement, and as if it was impossible for them to exist, if this cordial drop was taken from them. It was a disgrace to the English nation, and to the nature of man, to suppose that such an amusement could be regarded as indispensable by any set of men. Great writers had placed the summit of human happiness, but in the cottage of the peasant, surrounded with his smiling family. This was the happiness, and this the recreation, varied and combined with manly exercises abroad, which belonged naturally to the people of England, and he would not suffer them to be degraded by supposing, that, like bull-dogs, they had an instinctive desire for this sport.

「1802-May-24」 William Wilberforce “Diary Entry of May 24, 1802,” extracted in The Life of William Wilberforce, by Robert and Samuel Wilberforce (London, 1838).

24th. Town after breakfast, to which Mr. Mason, a minister at New York, came and much talk about religion, &c. in America. House on Bull-baiting Bill—Windham’s speech aimed expressly at me, though I had not spoken—quite prepared. I too little possessed, and having lost my note, forgot some things I meant to say, but was told I did very well. Bull-baiting Bill lost, 64 against 51. Sir Richard Hill’s foolish speech. Windham’s malignity against what he calls fanaticism. What casue have we for tankfulness that we enjoy so much civil and religious liberty!

「1802-Jun」” House of Commons, May 24, Bull-Baiting, Scot’s Magazine, 64 (1802-Jun) 511-512.

Mr. Wilberforce looked upon the practice of bull-baiting, as extremely cruel. It was a disgrace to the English nation, and to the nature of man, to suppose, that such an amusement should be regarded as indespensible by any set of men.

「1802-Jul」“Bull-Baiting in the House of Commons, on Monday, May 31「sic」.” Sporting Magazine 20 (1802-Jul) 187-190.

Mr. Wilberforce replied to Mr. Windham. He entered into a description of the cruelties practised on bulls to rouse them to a sufficient degree of fury, to gratify the barbarous wishes of their tormentors; and said, it was a disgrace to the English nation, to suppose that such an amusement could be regarded as indispensible to them.

「1802-Oct」”House of Commons, May 24, Second Reading of the Bill to Prevent Bull-Baiting and Bull Running,” Gentleman’s Magazine 92 (1802-Oct): 953-4.

Mr. Wilberforce spoke in favour of the bill; as did Mr. Newbolt

「1802」”House of Commons, May 24 on the Second Reading of the Bill to Abolish Bull-Baiting,” Annual Register 44 (1802): 168-72.

Mr. Wilberforce was of opinion, that this amusement fostered every bad and base principle of human nature; and he was sorry to find it had so able an advocate as his right honourable friend. He had made diligent inquiry into this practice, and, from the most respectable evidence, was convinced that shocking barbarities were practised to give the bull that degree of ferocity which was necessary for the amusement of the spectators. Sometimes the horns were sawed off and a pungent liquid poured into them: at other times, fire was used to stimulate their exertions. “Wretched indeed must be the condition of the lower orders of Englishmen, if all their happiness was confined to such barbaritres.” Such a libel upon the lower orders of Englishmen would be a strong argument indeed for jacobins to use. It has been a received, and justly approved of, notion, that the most brave were usually the most humane. How then could it be supposed, that a martial spirit could be cultivated by a practice as cowardly as it was cruel? for in this savage amusement, the bull is tied to a stake, and fights under every disadvantage. He was astonished that his right honourable friend could for a moment have compared it to horse-racing, where the animals who are contending suiter nothing at all. He conceived that, without cruelty or savage amusements, the people of England could find in their sports and athletic exercises sufficient recreations; he therefore was a friend to the bill.