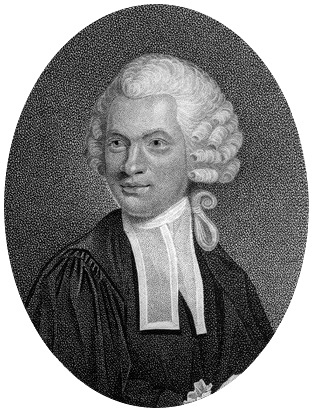

William Gilpin

Three Dialogues on the Amusements of Clergymen

「1796」 「William Gilpin」 Three Dialogues on the Amusements of Clergymen (1796; 2nd ed. London, 1797).¹

Well, then, said the Dean, we will begin with such amusements as are riotous, and cruel: and among these I should be inclined to assign the first rank to hunting. It is an unfeeling exercise, derived from our savage ancestors, who hunted at first for food and consigned the barbarous practice to their posterity for pastime (23).

So opposite to the mild serenity, which should characterize the clergyman 「is」 the cruelty exercised both on the animals, that pursue, and the animals, that are pursued—the horse pushed to the last extremity—the hound trained to the chase with savage barbarity—and the wretched fugitive agonizing in the extremity of distress. (24)

Do not call in argument to defend a pastime, which has no alliance with reason. Call it a wild passion—a brutal propensity—or any thing that indicates its nature. But to give it any connection with reason, is making a union between black and white.—But is it manly forsooth to hunt. Manliness, I should suppose, implies some mode of action, that becomes a man.…But to honour with the name of manliness, the cruel practice of pursuing timid animals to put them to death merely for amusement, is, in my opinion, perverting the meaning of words. (27-8)

I cordially allow no amusement to a clergyman that has any thing to do with shedding blood.—Besides, I think a peculiar cruelty attends this diversion 「of shooting」. You many wound, and main, as well as kill. My heart, I am sure, would be strongly affected—indeed, even my conscience—if I should make a poor animal miserable all the days of its life, for the sake of giving myself a momentary amusement. (45)

Man regulates his actions towards his fellow-men, by laws and customs. But certainly there are laws also to be observed between man and beast, which are equally coercive, though the injured party has no power of appeal. I fully accede, said I, Sir, to your code of criminal law between man, and beast. It is certainly power, not right, that we appeal to, in wantonly disposing of the lives of animals. (60-1)

I can have no conception of the humanity of a man, who can find his amusement in destroying the happiness of a number of little innocent creatures, sporting themselves, during their short summer, in skimming about the air; and without doing injury of any kind, pursuing only their own little happy excursions, and catching the food, which Providence has allotted them. But I have seen instances enough of this kind of cruelty to remove all surprise. (62-3)

¹ The second edition introduces the dialogues with a letter dated September 23, 1686 and suggests the work was a record of a conversation between Dr. Josiah Frampton and Bishop Edward Stillingfleet, written by Dr Josiah Frampton, in his own handwriting. A review of the book, in Freemasons’ Magazine, May 1796 「Google Books」, emphatically states that “this elegant tract, we can assure our readers, is written by Mr. Wilberforce.” An 1822 posthumous edition of Gilpin’s Sermons Preached to a Country Congregation, advertises the book as part of “A Catalogue of Mr. Gilpin’s Works Google Books」” (349) printed for Cadell and Davies. The Bibliotheca Piscatoria in 1883 reprints a letter from William Gilpin to his publishers「Google Books」(98) Messrs. Cadell and Davis, dated April 11, 1797 which states “As the subject is rather offensive, I don’t care to put my name to it, though I find it is mentioned in one of the reviews. But it is one thing to own and another to be suspected.” This work is considered to be that of William Gilpin.